Lady Tulle Rosemayne, a leader of society, beautiful, fascinating and accomplished, is the heroine of this romance. As the result of a wager with the irresponsible set to which she belongs, she compels the attention of John Sterne, film producer, reputed to be indifferent to women, who induces her to become a film actress. The setting of the story includes scenes in night clubs in London, in the Casino at Etretat, and wanderings in Paris…

I’ve been looking back over my notes on this book by Arthur Applin – one of a string of novels he wrote about London’s filmland in the 1920s (the others are listed in Ken Wlaschin and Stephen Bottomore’s fantastic bibliography of moving picture fiction, available online if you have access to the journal of Film History).

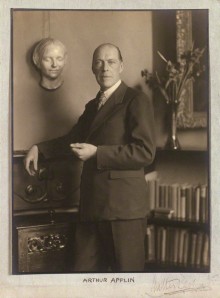

Applin is an interesting figure. His obituary in The Times says that he was born in Devon, trained as a lawyer, then gave up a legal career for the London stage, acting under a series of West End actor-managers. But he was best known as a novelist and dramatist. ‘He wrote frankly sensational stories’, said The Times, and he wrote lots of them – by my count, his back catalogue of plays and novels numbers well over 100.

Arthur Applin photographed in the 1920s, from the National Portrait Gallery website.

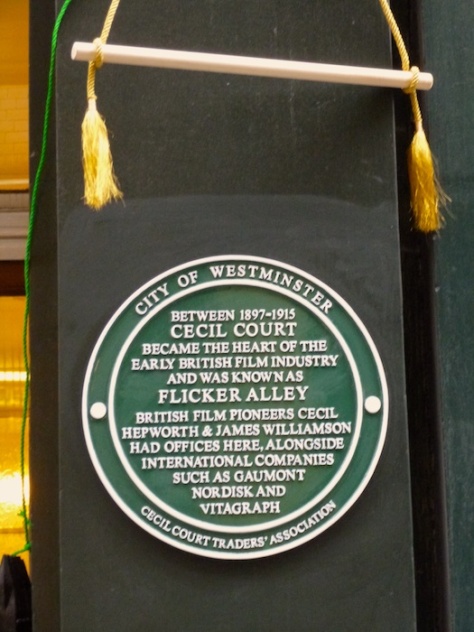

Many of Applin’s stories concern London’s entertainment industries, including musical comedy (in The Chorus Girl and Footlights) and the legitimate stage (glanced at in his filmland novel London Love). Whilst he didn’t start writing about the film business until the 1920s, his involvement with the British cinema went back at least as far as 1907, when he took part in a film designed to advertise his Evening News serial The Sons of Martha – an early (and, as far as I can tell, lost) experiment in tie-in movie marketing.

The view of London’s film culture Applin presents in The Path of a Star is, of course, fictional. It relies heavily on cliches and character types drawn from all sorts of early-twentieth-century popular literary genres. It is a heady mix – part showbiz expose, following the career of a young would-be star; part ‘Bright Young Things’ novel (published a year before Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies); and a large part romance, with a plot that centres on the clash of wills between the glamorous Lady Rosemayne (pictured salaciously on the front cover above) and the hard-nosed film director, John Sterne (the purple-suited man hovering on the edge of the spotlight).

What’s intriguing about Applin’s novel, at least from the perspective of someone interested in film history, is how cinema fits into this imaginary world: that is, which aspects of London film culture are brought into focus, and what kind of context they appear in.

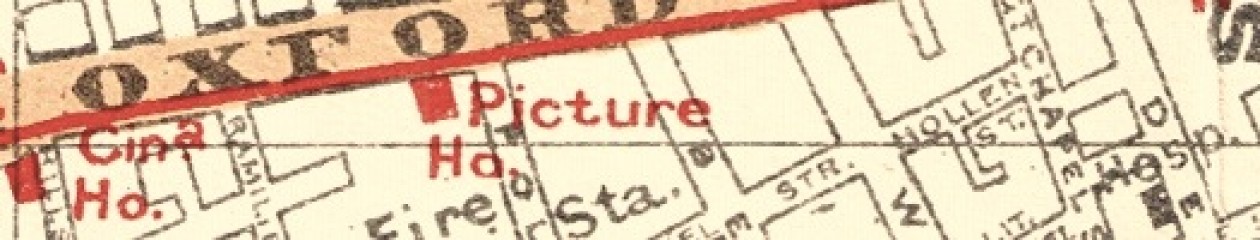

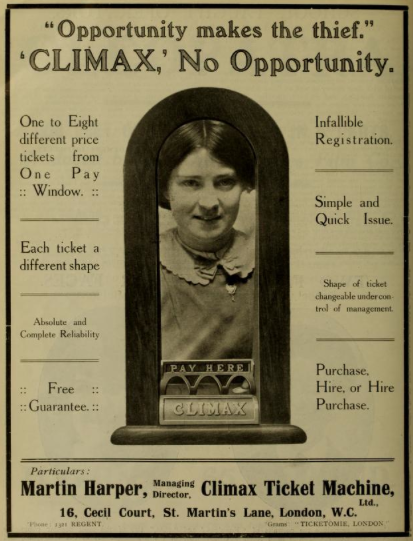

For a start, there’s a big emphasis in Applin’s story on the technology involved in putting a film together, and in the impact of modern technology more generally. Sterne, the director, rents offices in Piccadilly that are perched above a firm of motor car dealers. His studios, meanwhile, are situated in ‘a converted factory … tucked away on the left bank of the Thames’, and are themselves full of noisy camera equipment, lighting rigs and tangled wiring. What is the effect of all this newfangled technology? In Lady Rosemayne’s case, it leaves her feeling de-humanised – ‘an insignificant cog-wheel in that machine, one of the insignificant busy workers…’. It’s an image that recurs elsewhere in Applin’s literary London.

There are plenty of other fictional accounts of London’s film industry besides Applin’s. Here are a few more (hopefully easier-to-get-hold-of) stories dealing with London’s filmland:

- Katherine Mansfield, ‘The Pictures’ (1918). Mansfield’s short story follows a would-be actress through wartime London in search of a job. The names of the studios she visits – the Backwash Film Co. and the Bitter Orange Company – give a sense of the satirical bite that Mansfield brings to the subject. It was published in the magazine Arts and Letters, and again as ‘Pictures’ in Mansfield’s Bliss and Other Stories (1920). An earlier version of the story appeared in 1917 as ‘The Common Round’ in The New Age – available online at The Modernist Journals Project.

- Graham Greene, ‘A Little Place off the Edgware Road’ (1939). Greene spent a lot of time in cinemas during the 1930s as a film reviewer for the Spectator. Here, he uses an out-of-the-way picture theatre as the murky backdrop for a tale of death and madness. Published in the 1947 collection Nine Stories, and in various Greene anthologies since.

- Christopher Isherwood, Prater Violet (1945). Isherwood’s short, tightly sprung novel re-works his own experiences in the London film industry – working as a scriptwriter on British-Gaumont’s 1934 film Little Friend, directed by Berthold Viertel – as a reflection on studio politics and the rise of Nazism. The book is still in print.

I’d be interested to hear about other stories set in London’s cinema world, especially some more recent ones. Any recommendations?