Lately, I’ve been combing through a lot of film trade directories looking for information about old London cinemas. As anyone who has done research into British film history can vouch, titles like the Kinematograph Year Book are the yellowing, slightly dog-eared Wikipedias of the inner workings of the British film industry – full of interesting facts and figures, although sadly without the hyperlinks. (If you want a taster, the BFI have made the 1914 edition of the Kinematograph Year Book available online as a pdf.)

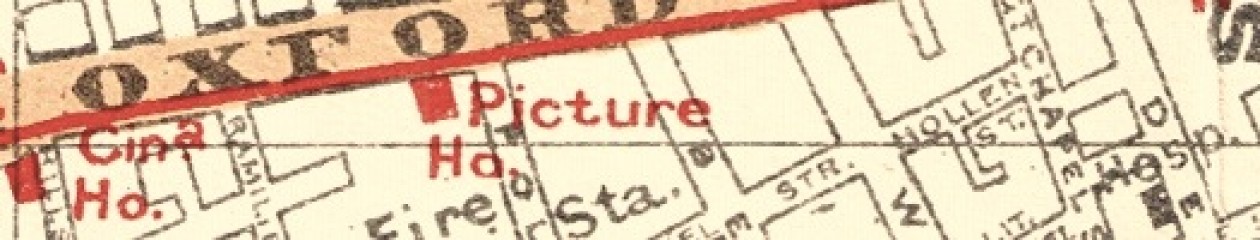

I was looking through the long list of London cinemas in the Kinematograph Year Book for 1919, when this entry caught my eye:

Institute of Hygiene, 33-4, Devonshire Street, Harley Street, W. 1. Prop[rietor]s, Institute of Hygiene. Res[ident] Sec[retary], Mr. A. Seymour Harding. Educational and Scientific Displays only, and by invitation chiefly. Largely used to illustrate lectures. No fixed programme or hours. First cinema installed in England for education work.

The entry seemed so incongruous (it’s sandwiched between the Imperial Theatre, Edgware Road, and the Abbey Picture Palace in Merton) that I thought it warranted further investigation. What films were the Institute of Hygiene showing, and why were they showing them in the first place? And was it really England’s first educational cinema? Here’s what I pieced together.

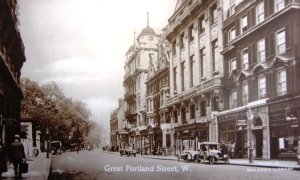

The Institute of Hygiene was founded in 1903, mainly to organize exhibitions about public health and preventative medicine. It also taught courses in hygiene for non-medical workers. The building at 33-34 Devonshire Street (a street that runs between Marylebone High Street and Great Portland Street) opened in the autumn of 1904.

33-34 Devonshire Street, London (Google Street View)

An issue of the British Journal of Nursing from the time explained that the central attraction at the Institute was ‘a permanent exhibition of hygienic products and appliances, and of articles of importance connected with personal and domestic hygiene’. Judging from the items mentioned in the BJN report, it seems that the Institute wasn’t averse to supporting its educational mission with a bit of product placement. Exhibits displayed ‘in the well-filled cases lining the walls’ included products from Nestlé, Cadbury’s, and other makers of ‘health’ foods and medical aids.

I can’t be sure that the Institute of Hygiene really did house the ‘first cinema installed in England for education work’, as the Kine Year Book suggests, but it seems like a reasonable claim. Films were shown there in the summer of 1912, with the intention of making them a permanent part of the exhibition. The trade magazine The Cinema reported on the first screenings in July 1912. The programme sounds like it wasn’t for the squeamish:

The Cinema and Hygiene

The use of the cinematograph as a means of education was illustrated at the Institute of Hygiene, when numerous pictures were exhibited, some in particular showing how disease is spread by flies. The ways in which flies carry disease by crawling on stagnant fish, afterwards feeding on the sugar in the house, and, alighting on the mouthpiece of a child’s feeding-bottle were shown by films. Other pictures, taken by a London doctor, indicated the most practical methods of rendering first aid in case of accident, while a series of industrial films afforded insight into the manufacture of “nut margarine,” meat extract, and other foods. Sir William Bennett, the President of the Institute of Hygiene, in inaugurating the educational cinematograph, said that while in America the cinematograph had been used for the demonstration of the details of surgical operations, and pictures of germ life had been shown in London, the instruction by this means had in the main been merely sporadic or accidental, and secondary to amusement.

This certainly seems like a pioneering use of moving pictures, even if William Bennett was selling his competition a bit short. There’s surely more than ‘accidental’ instruction at work in films like Charles Urban and F. Martin-Duncan’s series of ‘Unseen World’ pictures (the image at the top of this post comes from a 1903 ‘Unseen World’ instalment, Cheese Mites). But the point that early scientifically minded film shows tended to combine a large dose of amusement with their instruction is well taken: witness the famous Acrobatic Fly filmed by Percy Smith in 1910. Bennett was obviously trying to stress the seriousness of the Institute’s film screenings, and The Cinema went on to list some of the other ways that he intended to apply the new medium in the name of hygiene, like using microscopic images of germ life to teach food safety, or using film scenes to illustrate talks on domestic science and child-care.

I don’t know how long the Institute of Hygiene kept up their educational screenings. The organisation moved to new premises at 28, Portland Place in 1925, and merged with the Royal Institute of Public Health in the 1930s, by which time documentary science films had become more established as a genre. (Something discussed in Tim Boon’s book, Films of Fact.)

But, finding out about the Institute of Hygiene’s film work was a good reminder that, even when there was no shortage of dedicated cinemas around in London, films were still shown in a wide range of contexts, and for plenty of reasons other than commercial entertainment. In their recent edited collection of essays, Useful Cinema, Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson make a strong case for paying more attention to the history of what they call the ‘other cinema’: one that has always existed alongside the more familiar world of film-as-entertainment, but which instead set out to ‘transform spaces, convey ideas, [and] convince individuals’. Even if it wasn’t the direction that the mainstream film business ultimately took, the idea of cinema as a force for education did a lot to convince people in the early days, especially, that there was a future for moving pictures – and a useful future, at that.

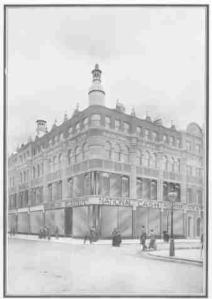

Since coming across the Institute of Hygiene’s entry in the Kine Year Book, I’ve found references to a few more non-theatrical venues in London (besides churches and local halls) that seem to have shown films on a regular basis. Situated at 223, Tottenham Court Road, was the London office of the National Cash Register Company. This was licensed to show films in its ground-floor hall ‘for trade purposes only’ as early as 1914. From what I can gather, it looks like this was the company’s national sales headquarters, so it’s possible that films were used to train employees in sales techniques.

National Cash Register Company office, Tottenham Court Road (c. 1904/Photographer unknown)

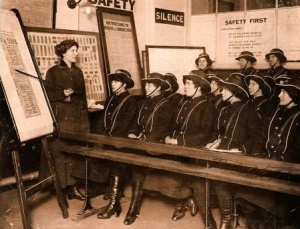

There’s a bit more information about the films shown in the second, equally unlikely film venue: the instruction depot of the London General Omnibus Company. This was located on Milman Street in Chelsea – here it is being used to instruct women omnibus drivers during the First World War:

(London Transport Museum Collection/Photographer unknown)

According to an article in The Times in May 1913, trainee drivers in the Milman Street depot were shown something like modern road safety films. ‘Cinematograph demonstrations were used in instructing the staff for showing how common forms of accident might be avoided’, with vehicles in the films ‘arranged to make close resemblance to actual accidents’ for extra authenticity.

These examples probably just scratch the surface. We’ve become accustomed to seeing moving images everywhere in cities now, but I wonder what other early film shows were going on in unexpected corners of London.

– –

The collection of essays edited by Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson is Useful Cinema (2012). Simon Popple and Joe Kember mention the idea of using film to train London omnibus drivers in their introduction to Early Cinema (2004), which also includes a discussion of some of the other potential applications for the cinematograph.