BBC Radio celebrated its ninetieth birthday last week. The BBC’s first public broadcast went out on 14 November 1922 from the company’s studio at Marconi House, on the corner of the Strand and Aldwych in central London. As the beginnings of the BBC overlap with the period of film history that I’m most interested in, I’ve been thinking a bit about the first impressions that radio might have made on London’s cinema world, and vice versa.

It’s often thought (and was sometimes said at the time) that the advent of radio posed a real threat to the livelihood of the film industry. Unlike cinema screenings, radio broadcasts could reach people in the comfort of their own living rooms – as long as the signal was strong enough – and were available daily for the price of a licence fee. Plus, in contrast to films, radio could bring events to people as they happened. In the 1920s, for instance, the BBC transmitted live relays of stage acts and musical performances from theatres and concert halls to wireless sets around the country. John Reith, the BBC’s first Director-General, summed up the company’s mission as bringing ‘the best of everything to the greatest number of homes’.

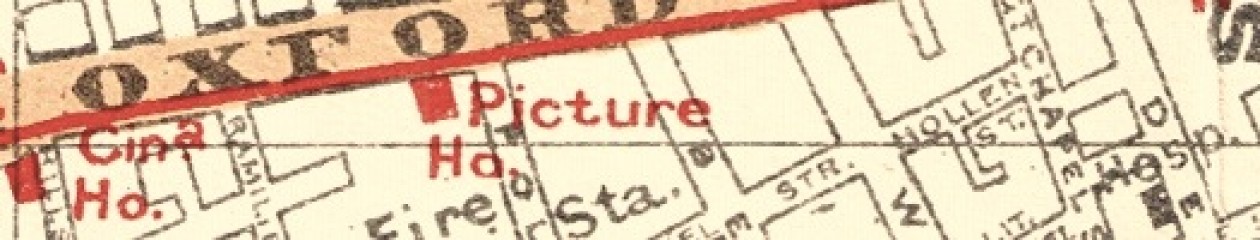

But, of course, radio didn’t kill off cinema. In fact, as historians like Jeffrey Richards have shown, the two industries found plenty of ways to work together, sharing stars and stories, and occasionally poking fun at each other’s peculiarities. And one of the first places that radio and cinema could be said to have met on friendly terms was in the studios of the BBC’s second home, Savoy Hill (pictured above).

The BBC relocated to Savoy Hill in April 1923. The building complex, which was also home to the Institute of Electrical Engineers (IEE), overlooked the Savoy Hotel and offered picturesque views of the Thames. Inside, the atmosphere was equally plush. The author Gale Pedrick later said:

Next to the House of Commons, Savoy Hill was quite the most pleasant Club in London. There were coal fires, and visitors were welcomed by a most distinguished looking gentleman who would conduct them to a cosy private room and offer whisky-and-soda.

The studios themselves were furnished with heavy drapes and thick carpets that sucked up the sound.

Studio 1 at Savoy Hill in 1928, from the BBC website

One of the regular visitors to Savoy Hill was the BBC’s first film critic, G. A. Atkinson. Atkinson, who also wrote film reviews for the Daily Express, was hired by the BBC in July 1923. Throughout the 1920s, he presented a fifteen-minute programme called Seen on the Screen, which went out once a fortnight at around 7pm on Friday evenings.

I haven’t come across any records of what Atkinson’s radio programme was like (although it would be great to find some), but his position as the BBC’s film critic was explained in a 1928 issue of the Radio Times:

More than ever in 1928, the movies are one of the symptoms of the way our civilization is going. No longer a crude device, interesting only for its novelty, or a ‘trick’ entertainment designed by the intelligent, the cinema as an art and as a cultural force has come to stay; and its importance as propaganda and as an industry is attracting the serious attention of legislators all over the world.

The films come pouring out of Hollywood in their thousands, and out of the English and Continental studios in their hundreds. No layman can see them all, but no one can afford to miss the significant ones. Hence the importance of listening to Mr. Atkinson’s expert and witty reviews of current productions in his fortnightly talks.

Atkinson’s Seen on the Screen was broadcast up to the end of the decade. At the same time, Savoy Hill also played host to the twenty-five-year-old film enthusiast, upcoming director, and son of a former Prime Minister, Anthony Asquith. Between 30 September and 4 December 1927, Asquith gave a series of five lectures on The Art of the Cinema. According to the accompanying programme notes published by the BBC, his first talk began by asking:

What is a film? Is it a genuine artistic medium? Or is it, like Broadcasting, just a way of bringing novels, plays or the latest news before a larger audience without changing their character – a sort of visual railway service for the art of literature and drama?

It seems that radio offered Asquith and his listeners another point of comparison (along with literature and drama) for understanding how cinema worked and what it could be. This comparison was surely going to be even more important with the transition to sound films that was then underway, and which would be more-or-less complete by the start of the 1930s.

There were other visitors from filmland, too. In his mammoth history of British broadcasting, Asa Briggs mentions that other ‘big names’ who featured in the BBC’s early output included the film-star cowboy Tom Mix, as well as Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. If that’s right, the wires and microphones of Savoy Hill would have given these Hollywood performers a taste of things to come in the era of the ‘talkies’.

BBC technicians at work in the 1920s

The BBC left Savoy Hill in May 1932 to move to their new purpose-built premises at Broadcasting House. The building now belongs to the Institute of Engineering and Technology (the successors of the IEE).

Plaque commemorating the BBC’s time at Savoy Hill

– –

There’s more information about the BBC’s time at Savoy Hill in the first volume of Asa Briggs’ History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom. Jeffrey Richards’ book, Cinema and Radio in Britain and America, 1920-1960, gives a bigger picture of the new medium’s relationship with film. The image of Savoy Hill at the top of this post was drawn specially for the Radio Times by Henry Rushbury in 1927.