‘Wardour-street is long and narrow, like a strip of film … Listen to the men walking away from one of the private cinemas hidden in the gaudy cliffs of offices, where they have seen a new drama on a six-foot screen: the life of the street swirls past them quite unnoticed. Listen to the people in cafes: nothing but celluloid.’[1]

Wardour Street, one of the main thoroughfares in Soho, was at the heart of London’s early ‘filmland’. Known sometimes as ‘Film Row’ or the ‘High Street of Film’, it first became a centre for the film business during the 1910s.[2]

Before it was linked to film, Wardour Street had other associations. For much of the 1800s, it was known primarily for its secondhand furniture brokers. Many of these dealt in woodcarvings and other architectural salvage from the churches and aristocratic homes of Europe.[3] Not all of these objects were as old or expensive as they were made out to be, and ‘Wardour Street’ gradually became synonymous with the trade in ‘spurious antiquities’.[4] (This in turn gave rise to the phrase ‘Wardour Street English‘ to describe pretentiously archaic speech.)

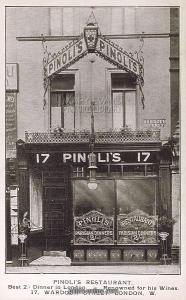

The street was also known for its music businesses, housing a number of musical instrument shops, as well as the sheet-music publishers Novello and Company.[5] By the end of the nineteenth century, it had absorbed further associations from Soho’s immigrant communities (chiefly French, Italian and Eastern European Jewish). In the popular imagination, the street conjured up suggestions of Italian restaurants, ‘lurid postcards and questionable French literature’, and ‘the music of the ubiquitous piano-organ’.[6]

The first film company to set up business in Wardour Street was that of Charles Urban, who moved into the building at 89-91 on 25 March 1908, naming it Urbanora House.[7] In 1910, Urban took over the building on the other side of the street at 80-82, which he named Kinemacolor House, in honour of his pioneer colour-film company.[8] Other film companies soon followed, including foreign firms looking for a London headquarters and British businesses opening their first permanent offices or re-locating from smaller premises (for instance, in Cecil Court).

By 1914, Wardour Street was home to more than 20 film companies, including Pathé Frères, who opened offices next-door to Urban at 84 and at 103-109, and the production firm Cricks and Martin at 101.[9] Harry Rowson (the co-founder of the ‘Ideal’ Film Company) moved into the premises at 76-78 Wardour Street just before the First World War. In his memoirs, he recalled how the price of insurance in London for companies with stores of (extremely flammable!) celluloid film stock was especially high. This encouraged film dealers to look for buildings with low rents, away from the main business districts, and sometimes to share premises in order to save on costs. Rowson’s company paid £650 a year to lease the ground floor and basement of ‘a modern fire-proof building’ on the corner of Meard Street, formerly occupied by printers. ‘I thought it the most conspicuous film office in London at that time,’ wrote Rowson, ‘situated in the heart of theatreland’.[10]

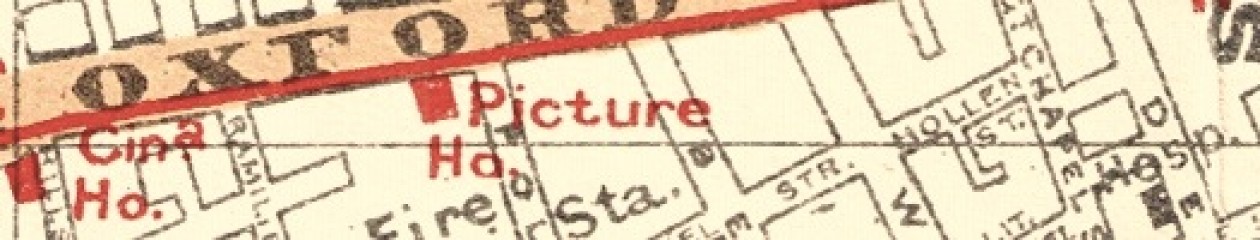

Wardour Street’s reputation as London’s ‘film centre’ was firmly established by the 1920s. There were around 40 film companies on the street in 1926, and many more nearby on Shaftesbury Avenue, Gerrard Street and Charing Cross Road. By 1929, the old Faraday electrical works at 146-150 had been rebuilt as the modern-style office building Film House.[11]

During this decade, the film industry on Wardour Street shared street space with other signs of ‘jazz age’ London. The Shim Sham Club at 37 attracted black Londoners and tourists, while the Tea Kettle became a popular destination for gay men and women.[12] Wardour Street was also associated with the Soho sex trade. At night, the street was ‘alive’ with prostitutes, according to the narrator of Patrick Hamilton’s 1929 novel The Midnight Bell.[13]

Wardour Street’s associations with the film business continued well after the 1920s. More offices were opened in the 1930s by Warner Brothers (at 135-141) and Arthur J. Rank (127-133). In the late-1940s, there were around 100 film companies along Wardour Street, and it could still be described by film writers as ‘the heart of the business’ in the 1960s.[14] By the end of the twentieth century, film businesses on Wardour Street had been joined, and to some extent replaced, by other media firms, including television and video companies and advertising agencies.[15]

Today, you can still see traces of the street’s historic connections with the film industry in the signs that remain on the front of several office buildings, including the former Urbanora House, Film House and Cinema House.

***

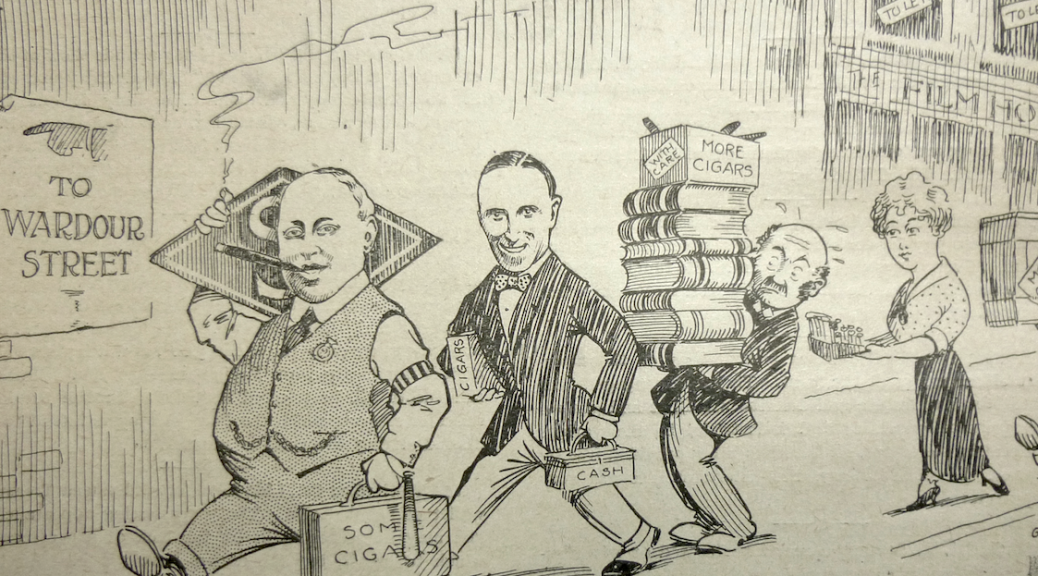

The cartoon at the top of the post is by G. Mitchell, and shows the London branch of the Selig Company preparing to move to Wardour Street in 1915 (from the Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly, 20 May 1915).

References

[1] James A. Jones, ‘Village Streets of London’, Evening News, 4 March 1932, p. 9.

[2] Ernest Betts, ‘When Films Came to Wardour Street’, The Times, 20 September 1967, p. 7; Nick Hasted, ‘London’s Little Hollywood’, Empire, no. 43 (January 1993), 40-41.

[3] John Harris, Moving Rooms: The Trade in Architectural Salvages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 37; J.H. Cardwell, et al, Two Centuries of Soho: Its Institutions, Firms, and Amusements (London: Truslove and Hanson, 1898), p. 188.

[4] P.H. Ditchfield, London’s West End (London: Cape, [1925]), p. 197.

[5] Leumas S. O’Neel, ‘W is for Wardour Street’, Eyepiece, 10:6 (September 1989), 15-16.

[6] Ditchfield, London’s West End, p. 197; Sophie Cole, Isobel in Wardour Street (London: Mills and Boon, [1910]), p. 80.

[7] Luke McKernan, Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897-1925 (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2013), p. 72. See also Rachael Low, The History of the British Film, 1906-1914 (London: Allen and Unwin, 1949), p. 99.

[8] McKernan, Charles Urban, p. 91.

[9] The Post Office London Directory for 1914 (London: Kelly’s Directories, 1914).

[10] Harry Rowson, “Ideals” of Wardour Street (unpublished manuscript, British Film Institute Reuben Library), p. 55.

[11] O’Neel, ‘W is for Wardour Street’, 16; ‘Wardour Street’s New Film House’, The Bioscope (30 May 1928), 89.

[12] Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 235, 242; Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2005), p. 69.

[13] Patrick Hamilton, The Midnight Bell (1929), quoted in Jerry White, London in the Twentieth Century: A City and Its People (London: Vintage, 2008), p. 314.

[14] O’Neel, ‘W is for Wardour Street’, 16; Betts, ‘When Films Came to Wardour Street’.

[15] Hasted, ‘London’s Little Hollywood’, 41.

One thought on “Wardour Street”