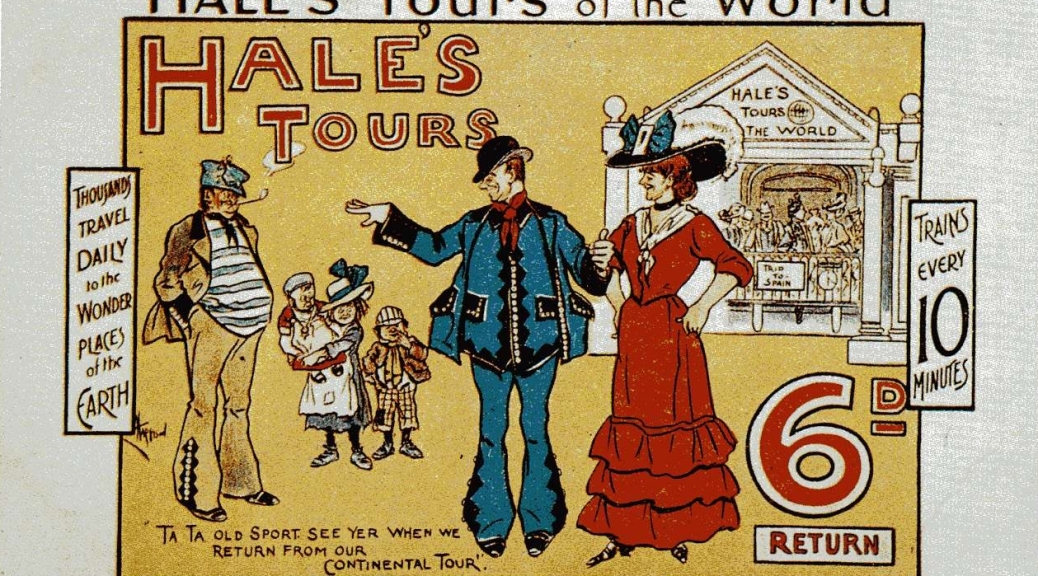

Will you go with me to HALE’S TOURS at 165, Oxford Street, W.? We can visit the Colonies or any part of the world (without luggage!) and return within fifteen minutes. Trains leave frequently from eleven to eleven. It is not only educational but intensely interesting.

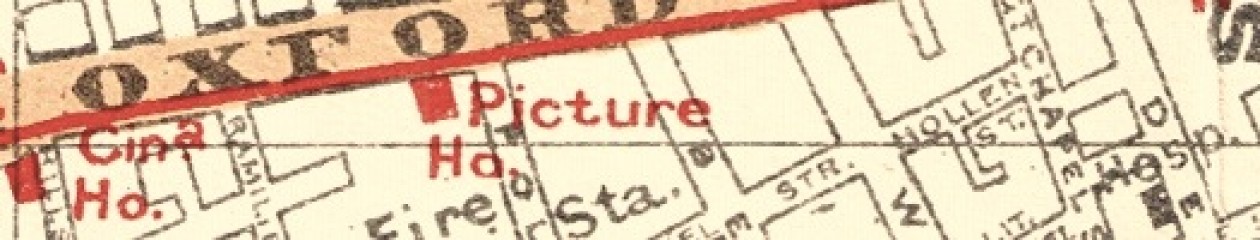

So read the message on the back of the postcard pictured above. It advertises one of two (possibly three) Hale’s Tours venues that opened on Oxford Street from 1906. Another was located in the building at number 532 Oxford Street near Marble Arch, and, according to Christian Hayes, there might have been a third on the corner with Argyll Street. By 1908, London had two more Hale’s Tours sites operating at Hammersmith Broadway and Kensington High Street.

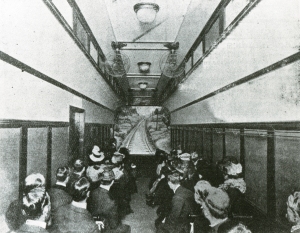

The wonder of the 15-minute round trip to Britain’s furthest-flung colonies and beyond was available to about 50-60 people at a time for the uniform price of sixpence. But how was it achieved? The attraction, first introduced at the 1904 St Louis Exposition by the entrepreneur George C. Hale, worked like a modern theme park simulator ride. The venue was made up of one or two carriages, decorated like the inside of a train, except for the fact that there were no windows. Instead, at one end facing the audience was a screen showing moving pictures of passing scenery.

Some of these moving pictures were repurposed or specially commissioned ‘phantom rides’. But there are also records of Hale’s Tours venues showing story films like Edison’s The Great Train Robbery. The effect wasn’t just visual. Although they never left the premises, Hale’s Tours carriages were designed to rock, tilt and vibrate to mimic the feel of a train journey. The ‘passengers’ at some venues were also treated to uniformed attendants, fans blowing a breeze overhead, and the sound of wheels, bells and whistles to add to the illusion.

Raymond Fielding has called Hale’s Tours an early example of cinematic ‘ultrarealism’. The columnist ‘Stroller’ writing for the Kine Weekly in 1908 thought so too:

In the journey through Rome, one could readily believe we were on a tram car; the rumbling of the wheels, the clanging of the bell to clear the traffic, the motion of the vehicle when rounding corners and the other effects were well-timed, free from exaggeration and as natural as one could desire.

But realism wasn’t the only thing on offer. Lauren Rabinovitz suggests that the effect of Hale’s Tours wasn’t just to transport viewers vicariously to distant places, but also to capture the sensations associated with modern technology – the same kind of miniature thrill offered by the rollercoasters on turn-of-the-century amusement parks.

If Hale’s Tours brought ‘the Colonies’ and a patch of the fairground within reach of shoppers along Oxford Street, there’s also an argument to say that the attraction opened up the West End to the idea of places exclusively showing moving pictures. By the time Hale’s Tours in Britain went bankrupt in 1908, there were at least two full-time cinemas in the district. One of these, the Theatre de Luxe on the Strand, had previously been trading as the Tivoli Tourist Station – a rival attraction to Hale’s. A little later, the former Hale’s Tours venue at 532 Oxford Street also became a cinema. While they lasted, though, Hale’s Tours weren’t just about the films. They sold themselves on a full, immersive experience.

References:

- Christian Hayes, ‘Phantom Carriages: Reconstructing Hale’s Tours and the Virtual Travel Experience’, Early Popular Visual Culture, 7:2 (2009), 185-198.

- Raymond Fielding, ‘Hale’s Tours: Ultrarealism in the Pre-1910 Motion Picture’, in John L. Fell (ed.), Film Before Griffith (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), pp. 116-130.

- Stroller, ‘Picture Shows As I See Them’, Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (1 October 1908), 481.

- Lauren Rabinovitz, Electric Dreamland: Amusement Parks, Movies, and American Modernity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).