Each comer who chooses may sport with the muses

Or notice the uses of genius or skill,

And find the employment of means for enjoyment

In modern Olympia all wishes fulfil.

(Mrs. W.A. Barrett, ‘Ode to Olympia’, 1886)

Exactly 100 years ago today, the First International Cinematograph Exhibition opened at London’s Olympia. The Exhibition ran from March 22 to 29, 1913, bringing representatives from various branches of the film business together under Olympia’s massive, barrel-shaped roof.

Progress and inclusivity were the main themes of trade press coverage of the event:

The programme set forth is most comprehensive in its nature, dealing with every phase of the industry, from the manufacture of the raw film to the finished image on the screen … Quite apart from its purely commercial side, the exhibition reveals, for the first time, the marvellous advance of cinematography. It is with no small pride that the Trade can regard its progress – unbroken, steady and continuous; and it is only fitting that its history and romance should be unfolded in such a manner.

(‘The Kinematograph Exhibition’, Bioscope, 13 March 1913)

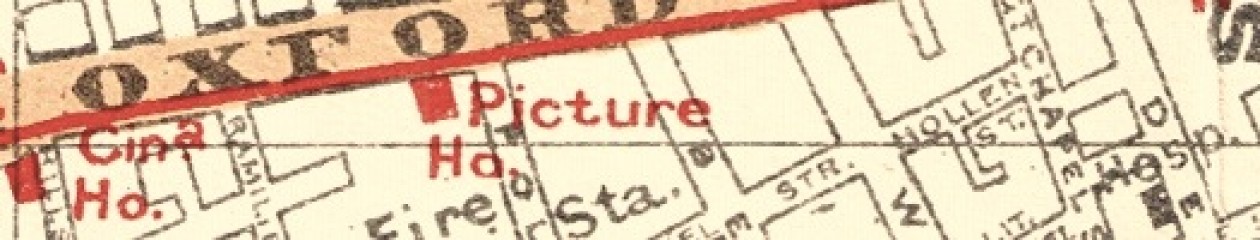

Advertisement / The Cinema, 5 February 1913

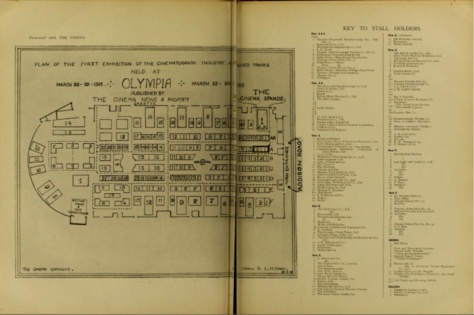

Despite some notable absences, the Exhibition was imagined as a microcosm of the industry at large, which (according to a trade journalist in The Cinema) had been advancing steadily and unstoppably across London and beyond:

whereas but a year or so since the number of firms dealing exclusively in films and cinema accessories ran but into tens, to-day the number is legion. Again, it is but a short space of time since Cecil Court was all too large to accommodate the members of the trade. Now the industry has grown to such proportions that Cecil Court, Charing Cross Road, Shaftesbury Avenue, Gerrard Street, Wardour Street, Rupert Street, Long Acre, Westminster Bridge Road, Gray’s Inn Road, Farringdon Road, and many other thoroughfares in the Metropolis itself, to say nothing of its suburbs, together with the large provincial cities and towns, contain representatives of the all-conquering cinematograph business. Not only have London firms opened branches further afield, but new concerns have sprung up in all directions…

Olympia was famous for its set-piece spectacles – Buffalo Bill’s ‘Wild West’ show, Imre Kiralfy’s recreations of Ancient Rome and Venice, Hagenback’s Wonder Zoo, not to mention R.W. Paul’s ‘Theatrograph’ displays. Like these, the Cinematograph Exhibition was designed to give visitors a chance to see a world they might not otherwise have the time or ability to reach:

…The British Isles, too, is dotted from end to end with cinema theatres, the owners of which in many instances are either too busily occupied or have neither the time nor the opportunity for periodical visits to London and have to rely for the knowledge they gain of what is doing in the cinema world upon the columns of the trade Press.

This class of person especially might be expected to look upon an exhibition in some central building and lasting for a week as a boon and a blessing…

(‘The Need for a Cinematograph Exhibition’, The Cinema, 1 January 1913)

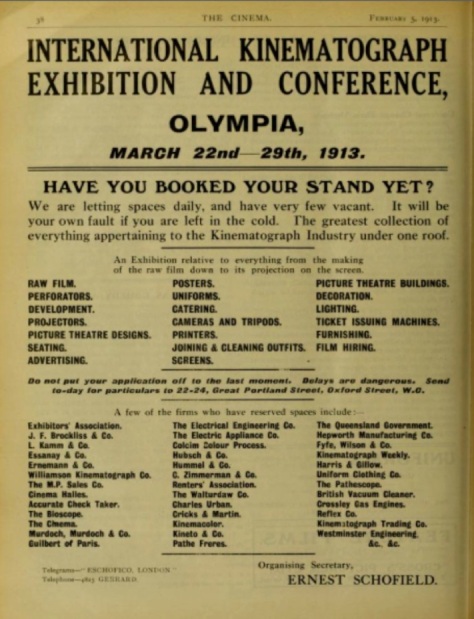

Map of the stands at the Cinematograph Exhibition / The Cinema, 26 March 1913

Visitors to the 1913 Exhibition could visit well over a hundred stands, all decorated in some way to attract attention (the ‘Essanay balloon’ was much remarked on). Some production companies also brought star guests with them:

The show has been visited by quite a number of picture celebrities. Many of the film producers have had their actors and actresses ‘on view’ at their stalls, and the Éclair Company, whose projection theatre has been thronged continuously, brought over Funnicus, Jane, and Softy, whose portraits are so well-known to all moving picture devotees to enable them to make a closer acquaintance with them.

(‘England Wakes Up’, The Cinema, 26 March 1913)

There temporary screening booths to show off new films and film technologies, and space was also given over to special contests. These included competitions for cinema projectionists and pianists, and one for would-be film actors. This was organized by Mr David Barnett and judged by Cecil Hepworth and George Cricks (of Cricks & Martin), and was said to have attracted more than 3,000 entrants to Olympia:

‘Amongst the competitors,’ said Mr Barnett, ‘were a German baroness and a Russian countess, and those who tried their skill in the depiction of the various emotions necessary for the little screen play arranged included men and women in nearly every calling. There were engineers, journalists, medical students, uniform nurses, market gardeners, bakers, and a large number of servants, and they hailed from all districts – Belgravia, Whitechapel, Maida Vale, and Soho. The majority were very earnest and painstaking, but a few capered about and made themselves generally most idiotic. One young gentleman, in his endeavour to express horror, acted in a most ultra-dramatic manner, and finally fell off the platform. A little comedy relief like that, you may guess, vastly amused the crowds who thronged to see the competitors.’

(‘Contest for Film Actors’, Era, 5 April 1913)

Besides these, there were representatives from institutions whose relationship to the film business was a bit hazier – groups like the Red Cross and the Boy Scouts, and organisations promoting the garden city movement or even emigration to Australia – but who presumably thought that the Exhibition represented a good opportunity to reach new audiences.

A heavy emphasis was placed on the potential educational value of moving pictures, with a special conference attended by such notables as the Headmaster of Eton. Morley Daintow, Assistant Manager of the Pulteney Council School in west London, gave his (extremely glowing) verdict on the Exhibition for the Bioscope:

My most lasting impression of the exhibition is as of one amazing wonder journey, similar to the experiences of my boyhood, when I first discovered some of Nature’s beautiful treasures. I congratulate the Trade on its achievements, and on the rare qualities of its representatives. At all stands I found men and women filled to the brim with fine enthusiasm for cinematogrpahy, and capable of so talking about it as not only to give wholesome pleasure but also useful instruction.

(Morley Dainow, ‘The Exhibition: A Teacher’s Impression’, Bioscope, 10 April 1913)

I don’t know whether the Cinematograph Exhibition succeeded either in its aim of generating business for the British film industry or promoting its usefulness as an educational tool. But it’s worth commemorating, I think, as an example of how the early film trade tried to project itself in the public eye, and as a reminder of the different kinds of activity that made up ‘cinema’ in Britain 100 years ago.

Olympia today / Wikipedia

– –

London’s Olympia is still in use as a venue. There’s more information about its history in John Glanfield’s book, Earls Court and Olympia: From Buffalo Bill to the ‘Brits’ (2003), and on the Olympia website. Here’s the full list of stall holders at the 1913 Cinematograph Exhibition as given in The Cinema’s souvenir map reproduced above:

Row A A A

Stall

- 1. Theatre – Hepworth Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (No. 1)

- 2. Bamforth & Co., Ltd.

- 3. Westminster Engineering Co., Ltd.

- 4. R.R. Beard

- 5. Theatre – Kinematograph Trading Co. (No. 2)

- 6. Pathéscope Demonstrating Room

- 7. Pathé Frères – Educational Department

- 8. Theatre – Pathé Frères (No. 3)

- 9-10. Theatre – Pathé Frères Offices

- 11. Theatre – Pathé Frères (No. 3)

- 12. Pathé Frères – Electrical Fillings Department

- 13. Theatre – National Cash Register

- 14. Theatre (No. 5)

- 15. Selfridges

Row A A

- 1. The Hepworth Manufacturing Co., Ltd.

- 2. Cricks & Martin, Ltd.

- 3. Heller & Co. (stencils)

- 4. Empty

- 5. Roll-up Metal Matting Co., Ltd.

- 6. The Navy League

- 7-12. Pathé Frères

- 13. W.&R. Jacob & Co.

- 14. Rowntree & Co., Ltd.

- 15. Garden Cities, Liverpool

- 16. Garden Cities & Town Planning Association

- 17. Cadbury & Co.

- 18. National Cash Register

Row A

- 1. Harris and Gillow

- 2. The Cinema News & Property Gazette, Ltd.

- 3. Keith Prowse and Co., Ltd.

- 4. Incorporated Association of Film Renters

- 5. Cinematograph Exhibitors’ Association of Great Britain, Ltd.

- 6. A.A. Godin

- 7. Williamson Kinematograph Co., Ltd.

- 8. Addressograph, Ltd.

- 9. Fyfe, Wilson and Co.

- 10. The Pictures

- 11. The Bioscope

- 12. Chivers and Son

- 13. Hudson, Scott and Sons, Ltd.

- 14. James Crosfield and Sons, Ltd.

- 15. Gas Light and Coke Co., Ltd.

- 17. Burroughs, Wellcome and Co., Ltd.

- 18. James Robertson and Sons.

- 19. Webb Lamp Co., Ltd.

- 20. Maurice F. Hummel

- 20a. Multicheck

- 21. F.R. Britton and Co.

- 22. Empty

- 23. Redio

Row B

- 1-2. The Walturday Co., Ltd.

- 3. Kinesounds, Ltd.

- 4-5. Newman and Sinclair, Ltd.

- 6. Murdochs

- 7. Wolfe and Hollander

- 7a. Uniform Clothing and Equipment Co.

- 8. G. Guilbert

- 9. The Accurate Check Taker, Ltd.

- 10. Criterion Plates, Films, etc.

- 11. The Electrical Engineering Equipment Co., Ltd.

- 12. A.E. Hübsch and Co.13. Jupiter Elekrophat

- 14. Ernemann

- 15. Muller and Co.

Row C

- 1-2. L. Kamm and Co.

- 3. The Topical Film Co., London

- 4. Alfred Hays

- 5. The Kinematograph

- 6. New Film Service

- 6a. Emil Busch Optical Co.

- 7. Harper Electric Pianos

- 7a. British Vacuum Cleaner Co.

- 8. Kineto, Ltd.

- 9. The Dictaphone

- 10. Whiting and Bosisto, Ltd.

- 10. The Imperial Suction Vacuum Cleaner

- 11. The Alumalite

- 12. The Acme Patent Ladder Co.

- 13. Joh Nitzsche, Leipzig

- 14. Ernemann

- 15. Muller and Co.

Row D

- 1. The British Uralite Co., Ltd.

- 2. Chex Ticket Machine Syndicate, Ltd.

- 3. The Globe Pen Co.

- 4. British Thomson-Houston Co., Ltd.

- 5. Columbia graphophones

- 6. R. and S. Neumann

- 7. [Empty?]

- 8. Cinema-Halles, Ltd.

- 9. Tella Camera Co.

- 10-10a. [Empty?]

- 11. Martin’s Feature Film Co.

- 11a. Gerrard Kinematograph Co.

- 12. J.J. Chettle & Co.

- 12a. J.M. Supply Agency

- 13-13a. [Empty?]

- 14. Big A Features

- 14a. Central Feature Exclusive Co.

- 15. Artograph

- 15a. The Award Film Service / Weymouth Exoress

- 16. [Empty?]

- 16a. Express Film Co.

- 17. [Empty?]

- 17a. Kinematograph Trading Co.

- 18. Peter & Cailler’s Chocolate

- 19. [Empty?]

- 20. Minerva Automatic Machine

- 21. Stentaphone Agency

- 22. [Empty?]

- 23. R.R. Exclusives

- 24. Rayflex Co.

- 25. Dustobo

- 26. N.B. Walters & Co.

- 27. S. Walker & Co.

Row E

- 1. Metropolitan Railway

- 2. [Empty?]

- 3. [Empty?]

- 4-6. Gas Light and Coke Co., Ltd.

- 7-9. Australia

- 10. Debrie

- 11. G. Mendel

- 12. P. Ruez

- 13-14. Museum

Row F

- 1. Great Western Railway

- 2. Post Office

- 3. Theatre Boroid (No. 11)

- 4. Essanay

- 5. [Empty?]

- 6. Theatre, Walturdaw (No. 10)

- 7. Richard Hornsby and Son, Ltd.

- 8-10. Australia

- 11. [Empty?]

- 12. Theatre Éclair Film Co. (No. 9)

- 13. F.C. Hart

- 14-16. Museum

Annexe

- 1. Red Cross

- 2. [Empty?]

- 3. Duty and Descriptive Lecture

- 4. Church Lads’ Brigade

- 5. “Christian Commonwealth”

- 6. Ragged School Union

- 7. “Church Newspaper”

- 8. [Empty?]

- 9. Theatre (No. 8)

- 10. Theatre (No. 7) Universal Screen Equipment Co., Ltd.

- 11. London Diocese Lads Brigade

- 12. Theatre (No. 6) Religious Educative and Social Welfare

- 13-14. Life Target and Shooting Gallery

Gallery

- 1. Pegamoid Leather Cloth

- 2. Cradley Carriage Co., Ltd.

- 3. Whiteley’s