After spending a while in the West End, I thought it was time that London Filmland ventured east. Following a tip-off from the erstwhile Bioscope, this post stops off at 100 Whitechapel Road, the former site of two film-related venues: the Rivoli and, before that, Wonderland. As a stalwart of the East End entertainment scene, there’s been a fair amount written about the place already, so this is an attempt to pull together information on some of the venue’s different encounters with film over the years.

Wonderland first opened its doors as a music hall in 1896, which was also when the site’s life as a film venue began. But it had been associated with entertainment since the 1830s, first as the Earl of Effingham Saloon, then as the Effingham Theatre, and later still as the East London Theatre (which burned down in 1879). Like the Pavilion Theatre down the road, the venue seems to have depended mainly on local working-class and immigrant (especially German and East European) audiences, being too far away from the city centre to attract the West End’s more well-heeled, floating clientele.

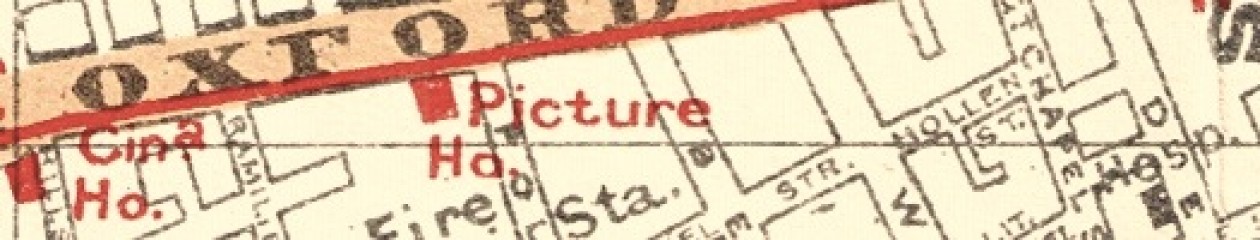

A Whitechapel street scene / Yoshio Markino, from The Charm of London, 1912

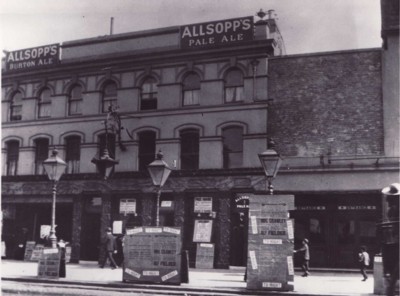

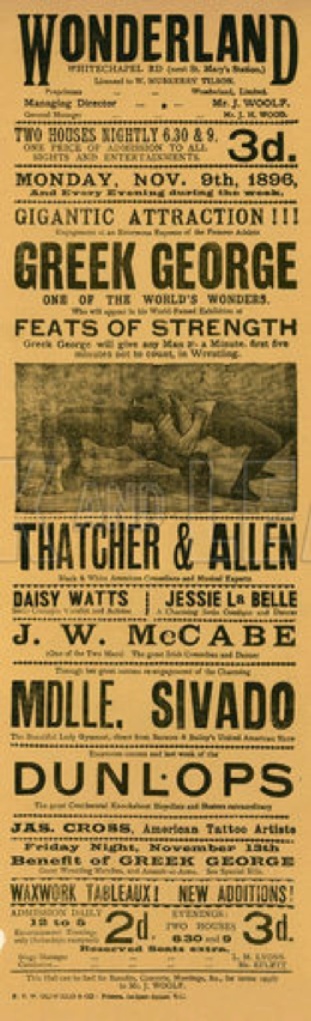

The proprietor of Wonderland was Jonas Woolf, who spent £5,000 fixing up the building to comply with London County Council regulations, and who went all out to compete with the other local music halls. When Wonderland opened, Woolf traded heavily on the eclecticism and exoticism of his acts, putting together what the Era called a ‘curious exhibition of freaks’ for the hall’s first programme.

Call for acts for Wonderland / The Times, 1896

Woolf also tried to drum up local support through a series of competitions, some of them designed to appeal to particular professions or social groups. So, there were contests for basket carrying (for market traders), carving up sheep (for butchers), shaving (for barbers), pram racing (for mothers), as well as others for singing, washing clothes, crawling, standing upside down, and more inventive tests of skill involving kicking a football through a hoop, and eating treacle from a swinging bread roll.

Moving pictures were first shown at Wonderland in April 1896 in the form of R.W. Paul’s ‘Theatrograph’. Sadly, the show wasn’t a success, and managed to land Woolf in Clerkenwell County Court. As the Era reported in July that year, Paul was suing Wonderland, Limited, for failing to pay the sum of £22, 10 shillings – equivalent to three weeks’ rent of electrical accumulators to power the ‘Theatrograph’ kit. Woolf’s defence was that the moving pictures had come out ‘blurred and indistinct’. It was said that the audience at Wonderland ‘used to hiss the performance, and many people had demanded and received back their money’.

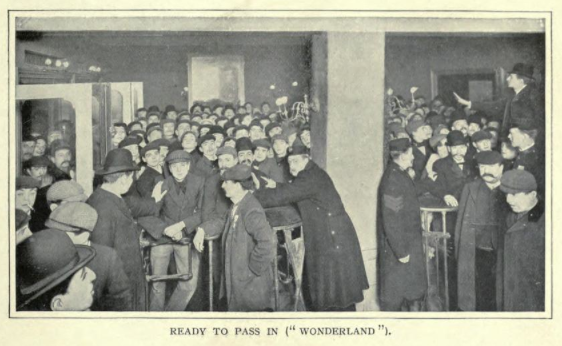

Patrons of Wonderland / Photographer unknown, from H. Chance Newton, ‘Music-Hall London’, 1902

In court, Woolf went on to state that the ‘Theatrograph’ was booked as the star attraction on Wonderland’s bill, and so its poor performance had done significant damage to the venue’s earnings and reputation. This line of argument resulted in the following bizarre exchange between Woolf and Paul’s barrister, Mr. Gill, which also gives a sense of the variety acts that the ‘Theatrograph’ would have appeared alongside at the Wonderland:

Mr Gill (to Mr Woolf) – You say the “Theatrograph” was your star attraction, and that the losses of your music hall were due to its failure? Witness – The rest of the programme was mere padding.

Mr Gill (reading from a poster) – Do you call the Bear Lady padding – “A native of Africa, full grown, whose arms and legs are formed in exactly the same manner as the animal after which she is named?” – Witness – Yes, the Bear Lady was padding.

Mr Gill – And the Fire Queens, “who have appeared before the Prince of Wales, the King and Queen of Italy, and King of Portugal, who pour molten lead into their mouths, lick red-hot pokers, and remain several minutes enveloped in flames and fire?”

Witness – Yes, the Fire Queens also were padding.

Mr Gill – I am not surprised that these monstrous exaggerations damaged your business. It was not the theatrograph.

After all this, the judge decided that Woolf was at fault for failing to provide sufficiently powerful lighting, and ordered him to settle his debt to Paul.

Poster for Wonderland, November 1896 / Peter Jackson Collection (lookandlearn.com)

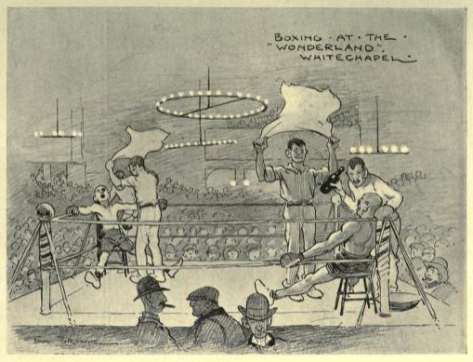

Undeterred, Wonderland carried on showing films on and off into the 1910s. But, as the venue continued to diversify the entertainments on offer, it became best known as one of the East End’s premier boxing halls. Robert Machray gives a virtual tour of a Saturday night boxing match in Wonderland in a guide to The Night Side of London from 1902.

You pass into the building – at the door stands a solitary policeman. You pay, perhaps, the highest price, three shillings, which entitles you to a seat on the stage. You have come a quarter of an hour before the time announced for the beginning of the first match, but the vast building is already packed, except on the stage, where there is still room. And what a dense mass of human beings there is!

Machray estimated that there were upwards of 2,000 people crammed into the auditorium. To add to the activity, there were also vendors selling refreshments. During the match, patrons could purchase oranges, cigarettes, soft drinks, plus ‘the greatest of East End delicacies, the stewed eel’.

‘Boxing at the “Wonderland”, Whitechapel’ / Tom Browne, from Robert Machray, The Night Side of London, 1902

The venue burned down (for the second time) in August 1911, sparking rumours that Woolf had been the victim of an arson attack from a former business partner. The more likely culprit, though (according to The Times), was none other than a film projector, which was being tested in the afternoon for an evening show, and had apparently been set alight by some faulty wiring. (Woolf later told the press that the fire had started in a side gallery, and not the projection booth.)

Wonderland seems to have been up and running again by the mid-1910s, and it’s listed as a film venue in the trade directories on and off until 1917. But in 1921 it was reinvented once more – this time as the Rivoli Cinema.

The Rivoli was one of the East End’s first ‘super cinemas’, a new breed of large-capacity film venue, and one of the earliest of its kind to be built anywhere in the UK. The remodelled outside of the Rivoli promised grandeur, with neo-classical columns and arches:

Inside, there was an upper circle over the stalls, providing seating for over 2,000 people, and a large stage for variety acts:

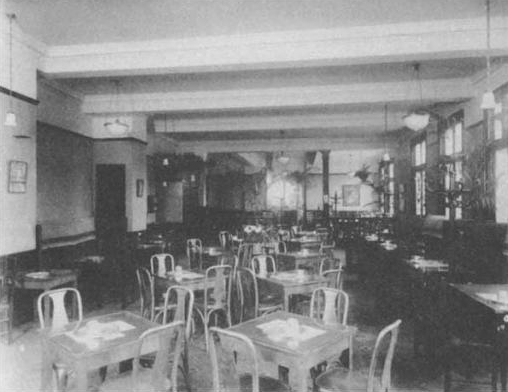

There was also a tastefully appointed café:

Stanley Collins provided a lengthy, first-hand account of his time working at the Rivoli in the 1920s in a series of articles for the in-house magazine Gaumont-British News in 1932 (handily reproduced in a 2001 issue of the journal Picture House). Collins had been working as secretary to the US film producer and theatre manager Walter Wanger during his stint at the Covent Garden Opera House. When Wanger announced that he was taking over the Whitechapel Rivoli, Collins followed him, and was duly appointed Assistant Manager, with Hal Lewis as General Manager.

As Collins remembered it, the Rivoli under Wanger and Lewis’s management became well-known for high-quality film programmes and variety acts. ‘The cream of the variety world, at some time or other,’ he wrote, ‘trod the boards of the Rivoli’s fine stage’. Collins was less effusive about the Rivoli’s audiences (‘not exactly genteel’), claiming that fights inside and outside the cinema were frequent. Collins had fonder memories of working with Ernest Trimmingham, known as ‘Trim’, a Bermudan playwright and stage actor then living in the East End, who (as Stephen Bourne shows) was probably also the first black actor to appear in British films. During Collins’s time as Assistant Manager, ‘Trim’ was acting as ‘a sort of “barker”‘ for the Rivoli, advertising the cinema around the neighbourhood. He also did a turn on the variety stage there to an enthusiastic house.

Around 1924, Hal Lewis was replaced as manager by Billy Stewart, who set about revamping the place. Here’s Collins again:

He [Stewart] put the staff into smart new uniforms, and engaged five little blondes to open the main swing-doors to the theatre. Their smart blue pageboy tunics, short skirts, patent-leather leggings, white gauntlets and jaunty peak caps gave quite a “ritzy” touch to the front of the house. Even the four pageboys were supplied with white spats and gloves! Personally, I felt that Billy was overdoing it for Whitechapel, but I was wrong. Before long, people came from the West End to the Rivoli, so smart had the house become. The difference was so marked, in fact, that the ‘locals’ ceased their habit of dropping peanut shells under the seats, and the house at the end of a performance no longer resembled Brighton beach!

There’s a tension in Collins’s description between ‘West End’ and ‘East End’ values. I wonder how the ‘locals’ he talks about took to these changes in décor and decorum? Did they welcome the presence of a more ‘ritzy’ venue on their doorstep, or were they nudged out by the new house policy?

The Rivoli was taken over by the United Picture Theatres circuit in 1928 and by British Gaumont in 1930. But, despite all this, like the venues on the site before it, the cinema continued to have some social connection to Whitechapel residents. Research by Gil Toffell has shown how it was especially important for the East End’s Jewish audiences. In the 1930s, it was one of the few places in London where Yiddish sound films were shown – films like The Voice of Israel (1930) and Uncle Moses (screened there in 1938). The auditorium was also known to host Rosh Hashanah services when the local synagogue proved too small to accommodate the number of worshippers.

The Rivoli stayed open until 1940, when it was destroyed in an air raid. The bombed-out building was finally demolished in the 1960s. The site at 100 Whitechapel Road is now a Citroen car dealership, next door to the East London Mosque.

100 Whitechapel Road / Google Street View

– –

References:

The following sources contain information about Whitechapel, Wonderland, the Rivoli, and people associated with the venues. Feel free to add more in the comments section, if you know of any.

- ‘The “Theatrograph” in Court’, Era, 18 July 1896.

- ‘”Wonderland” Burnt Out’, The Times, 14 August 1911.

- Arthur Lloyd, ‘Pavilion Theatre and Wonderland, Whitechapel Road, Stepney’.

- Bourne, Stephen, Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television(London: Continuum, 2001), pp. 7-9.

- Cinema Treasures, ‘Wonderland’ and ‘The Rivoli’.

- Collins, Stanley C., ‘Two Years at the Rivoli’, Picture House, 26 (2001), first printed in Gaumont-British News, beginning November 1932.

- Davis, Jim, and Victor Emiljanow, Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840-1880 (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2001).

- Eyles, Allen, Gaumont British Cinemas (London: BFI, 1996), p. 221.

- Hyatt, Alfred H., ed., The Charm of London: An Anthology (London: Chatto & Windus, 1912).

- London Project, ‘Wonderland’.

- Machray, Robert, The Night Side of London (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1902).

- Newton, H. Chance, ‘Music-Hall London’, in Living London, ed. George R. Sims (1901-1903), vol. I, section ii, pp. 222-228.

- Nipperpatdaly, ‘East End Boxing Was Floored by the Flames’.

- Summerfield, Penelope, ‘The Effingham Arms and the Empire: Deliberate Selection in the Evolution of Music Hall in London’, in Popular Culture and Class Conflict, 1590-1914: Explorations in the History of Labour and Leisure, ed. Eileen Yeo and Stephen Yeo (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1981), pp. 209-240.

- Steelcroft, Framley, ‘Queer Competitions’, Strand Magazine, July 1897, 55-65.

- Toffell, Gil, ‘“Come See, and Hear, the Mother Tongue”: Yiddish Cinema in Interwar London’, Screen, 50:3 (2009), 277-298.

- Toffell, Gil, ‘Cinema-going from Below: The Jewish Film Audience in Interwar Britain’, Participations, 8:2 (2011), 522-538 (pdf).