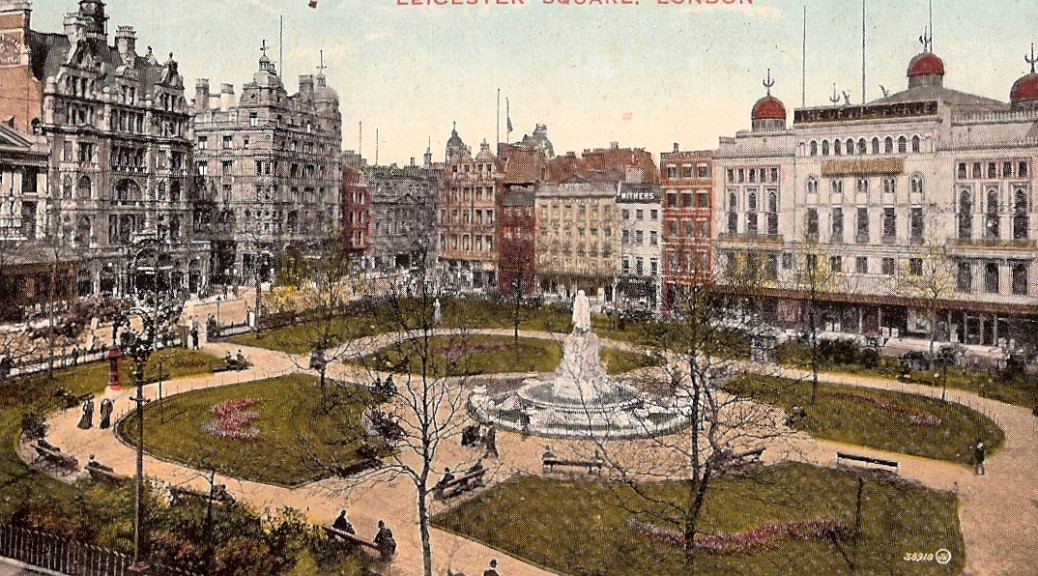

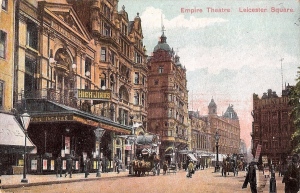

Featured image: The north and east sides of Leicester Square from a postcard, ca 1903. The caption on the back reads: ‘Leicester Square. – Popular centres of refreshment and amusement abound in and around this charming green spot amidst the roaring streets. The Alhambra [pictured on the right], the home of brilliant ballet and variety entertainment, appears in the view, its Moorish grandeur looking strangely out of place amongst so much typical English architecture.’

I’m celebrating this blog’s first birthday with a trip ‘up West’ to one of the focal points of London’s filmland, Leicester Square. I also wanted to spend a bit of time here because I’ve been thinking about a question posed early in 1913 by a writer in one of the film trade papers: who was the audience for the first West End cinemas?

What the writer, Samuel Harris, actually wanted to know was whether there was a public demand for the expensive new picture palaces appearing on thoroughfares like Oxford Street and Shaftesbury Avenue. London theatregoers, he thought, had little choice but to travel to the West End if they wanted to watch the latest stage shows. But, seeing as there were ‘far more cinema theatres by hundreds outside the West-End than there are theatres and music-halls’, and given that these cinemas generally showed the same films as those in the West End, would cinemagoers from the suburbs or further out really go the extra mile to get something already available closer to home? Plus, if West End cinemas did manage to attract regular patrons, would these be the same people who went to West End theatres and music halls? In fact, he wondered, ‘Where do the West End regular theatre audience come from’ in the first place?

Harris was an estate agent whose firm brokered some of the big West End cinema projects, so he had a personal interest in asking these questions. I’m not able to answer them all yet. But a trip to Leicester Square might provide a bit of background on the West End as a destination for amusement-seekers.

Originally, Leicester Square was a residential spot. It was laid out and railed off from the surrounding Leicester Fields in the seventeenth century as a decorative accompaniment to the stately Leicester House. During the eighteenth century, it was hedged in by private houses – home to aristocrats and artists like William Hogarth and Joshua Reynolds. There were a few shops by this point, but in the nineteenth century commerce more or less took over. Residences made way for a wave of hotels, shops, exhibition centres, institutes and museums. Compared to some of London’s other squares, this was quite a dramatic transformation. The architectural historian E. Beresford Chancellor wrote that, ‘from being as much a private square as those of St. James’s or Bloomsbury, Leicester Square has become as much a public “place” as Trafalgar Square or the Place de la Concorde’.

This commercialisation points to something that was happening more widely in the West End at the time. Wealthy residents were moving out of the area to the suburbs, leaving the major theatres (including the old patent theatres at Covent Garden and Drury Lane) in need of a new audience. In their book on nineteenth century theatregoing, Jim Davis and Victor Emeljanow suggest that the Great Exhibition of 1851, which attracted upwards of 6 million tourists to London in the space of five months, gave theatre managers a feel for how they might make up for the loss of their old, local clientele. The solution managers came up with (according to Davis and Emeljanow) was to turn the West End into a kind of theatrical ‘theme park’, unique enough to entice tourists into the area. In Leicester Square, an important model for capitalising on the emerging tourist trade was provided by James Wyld, whose Great Globe stood in Leicester Square gardens from 1851 and continued to pull in visitors for several years after the Exhibition closed.

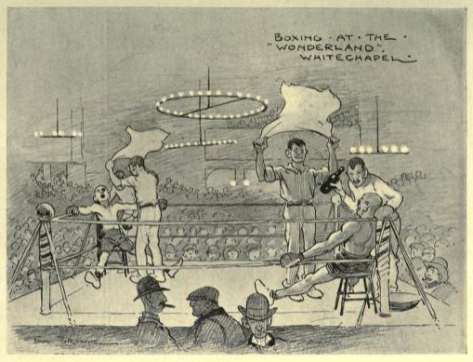

The Great Globe vanished (replaced, until the 1870s, by what Beresford Chancellor described grimly as ‘a wilderness … and a last resting-place for dead cats’), but other attractions sprung up in its place. By the turn of the century, Leicester Square was dominated by two huge variety theatres – the Alhambra on the east side, the Empire on the north – plus Daly’s Theatre just off the square on Cranbourn Street. There was also the Queen’s Hotel, the Hôtel Cavour (the first of the square’s ‘foreign’ hotels), and a number of shops, clubs and restaurants.

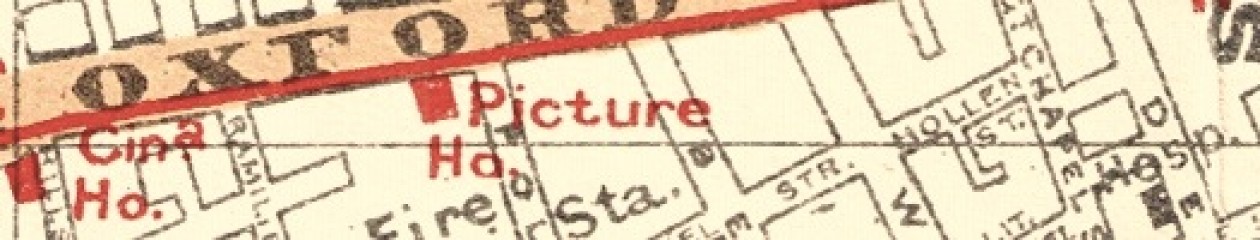

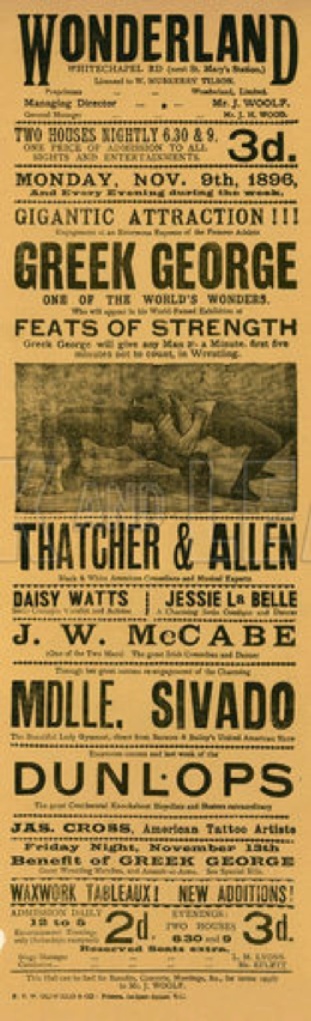

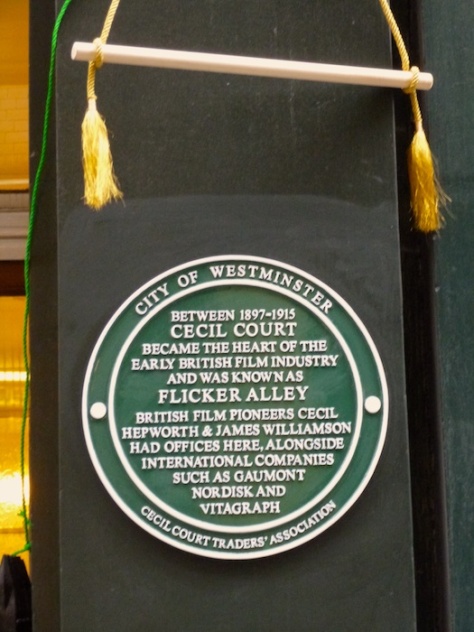

The Alhambra and the Empire both showed films from 1896 as part of their variety programmes. But the first dedicated cinema, the Circle in the Square (also known as the Bioscopic Tea Rooms, and afterwards Cupid’s and the Palm Court), opened in 1909 next to the Alhambra. This was the only full-time film venue on the square until the Empire was rebuilt as a flagship cinema for MGM in 1928. The Alhambra was knocked down to make way for the Odeon in 1936. But there were other early cinemas nearby: the Cinema de Paris on Bear Street opened in 1910, and the much grander West End Cinema Theatre on Coventry Street opened – in the presence of royalty, no less – in 1913.

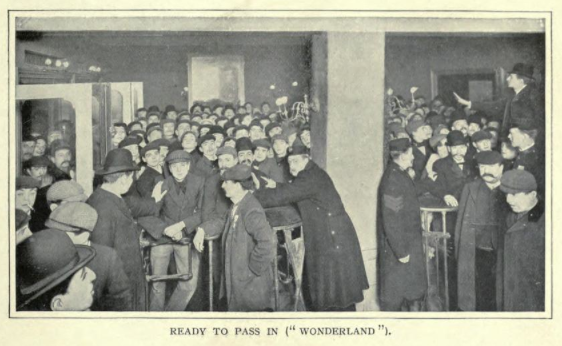

Who might have been in the audience at these early Leicester Square cinemas? We can guess that foreign and provincial tourists, who visited the Empire and the Alhambra, and who stayed in the area’s hotels, might have also visited the cinemas. So, too, might Londoners in search of some controlled naughtiness. Judith Walkowitz sums up the prevailing culture of Leicester Square around this time as a mixture of ‘foreigness’ and British chauvinism: ‘Sufficiently cosmopolitan to appeal to foreign tourists … as well as to Londoners desirous of a touch of the Continent’. The Cinema de Paris on Bear Street could have been named with exactly these potential customers in mind.

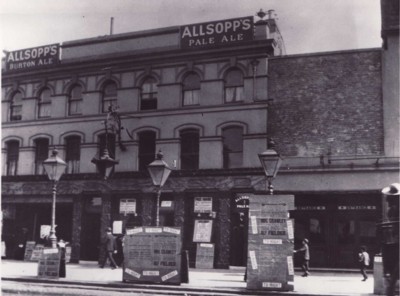

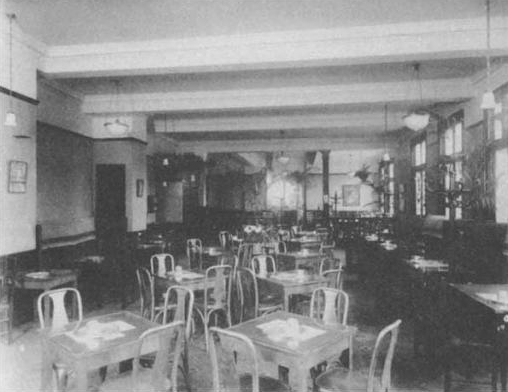

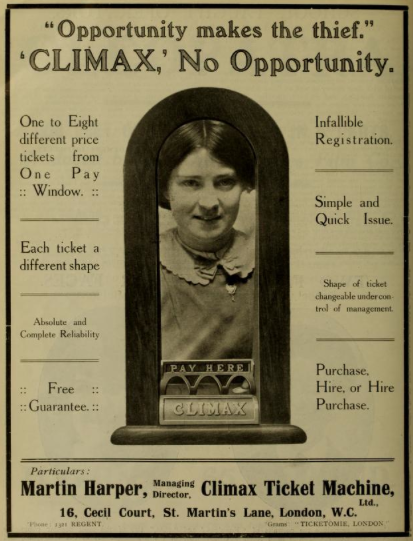

Early Leicester Square cinemas were also well placed to appeal to passing trade. When they opened, the Circle in the Square and the West End Cinema operated a policy of continuous performance, showing films Monday to Saturday from about midday to midnight (and Sundays from 6pm). Positioned next to the Alhambra and the Empire and near the theatres on Shaftesbury Avenue, they would have been in a good position to attract variety patrons waiting for the 8pm performance or playgoers on a night out. During the day, they might have been a stopping point for shoppers en route between the big department stores on Oxford Street and Regent Street and the railway stations at Charing Cross and Waterloo. If they wanted to, passersby were also able to come in just for something to eat: the Circle in the Square had tea rooms adjoining and underneath the auditorium and the West End Cinema had a ‘Balcony Tea Lounge’ that served drinks and snacks.

All this suggests that cinemas could have shared the audience for other West End amusements without necessarily competing with them directly, in the same way that earlier Leicester Square attractions were able to cash in on the tourist trade drummed up by the Great Exhibition. What I’d still like to know, though, is whether these early film venues brought any new visitors to Leicester Square – perhaps people who might not have been able to afford to go out there otherwise, or who might have been put off by the social niceties of West End theatregoing. Tickets at the West End Cinema were as pricey as those at the nearby theatres, but the Circle in the Square seems to have been a bit cheaper. There, customers could watch a film and enjoy a cup of tea for the same price as a seat in the pit at the Alhambra. Could the arrival of film have opened up the West End to new audiences – new ‘cinematic’ tourists?

There’s more digging to be done before I feel confident answering this question. But, as Leicester Square emerges from its recent multi-million-pound makeover, carried out (according to mayor Boris Johnson) to guarantee its status as a ‘beacon for world premieres and the stars of the silver screen’ and, consequently, as a ‘must-see destination’ for tourists, it’s interesting to think back on what impact film might have been having on the square and its visitors 100 years ago.

References:

- Samuel Harris, ‘Thoughts that Make Us Pause and Ponder – No. 2’, The Cinema (29 January 1913).

- E. Beresford Chancellor, The History of the Squares of London (London: Paul, Trench, Trübner: 1907).

- Jim Davis and Victor Emeljanow, Reflecting the Audience (Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2001).

- Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

- Lauren Turner, ‘New Look Leicester Square Opens’, The Independent (23 May 2012).