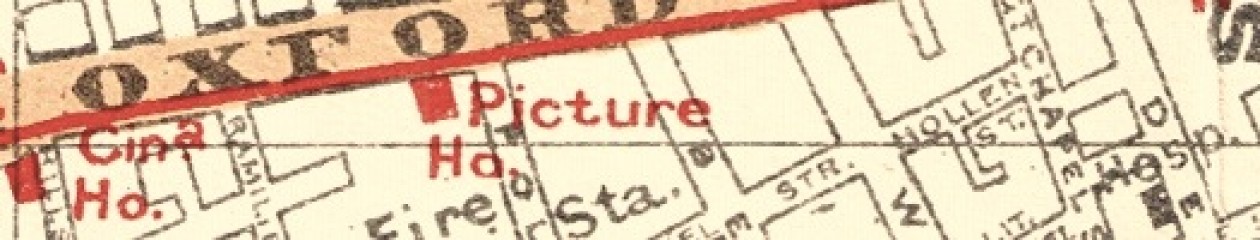

On a trip to the Haringey Archives a little while ago, one of the archivists showed me a collection of material about Alexandra Palace. I was looking for information about an early film studio on the premises (more of which another time), but what caught my eye was a pamphlet about conditions in Alexandra Palace when it was being used as an internment camp for German civilians during the First World War.

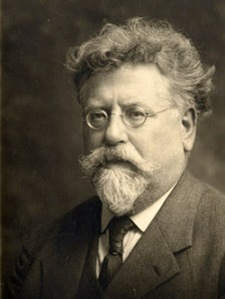

Included in the pamphlet (produced by the Anglo-German Family History Society) was an essay on life in the camp written by Rudolf Rocker. Rocker had moved to London from Germany, by way of Paris, in the 1890s, since when he had become an important figure in the anarchist scene of the East End. He was also influential in international politics as the editor of the radical Yiddish newspaper Arbeter Fraint (‘Worker’s Friend’).

Soon after the outbreak of war, Rocker, along with 3,000 other German-born residents, was arrested and interned in Alexandra Palace as an ‘enemy alien’. Several years into his internment, he was asked by the camp’s commandant, Major Mott, to write a first-hand account of his experiences. Rocker was deported to Germany in 1918 before he could finish the essay, but his rough drafts and notes were preserved and edited together by ‘W. Stz’ and Rocker’s son, Rudolf Rocker, Junior.

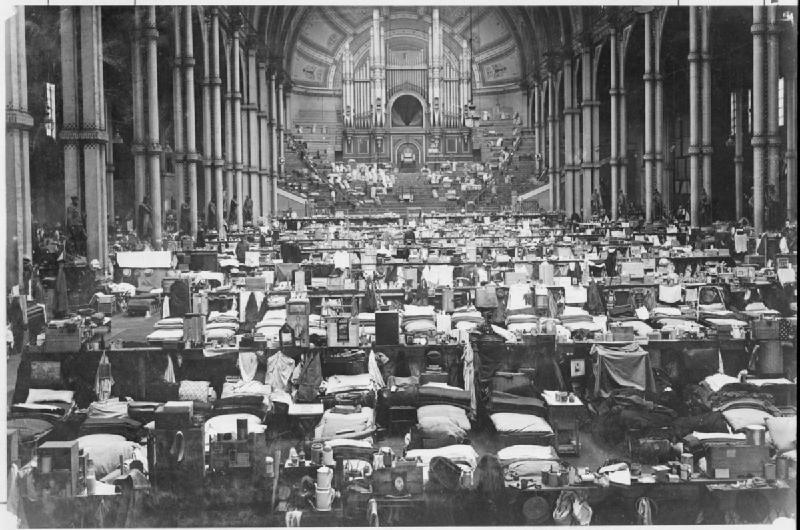

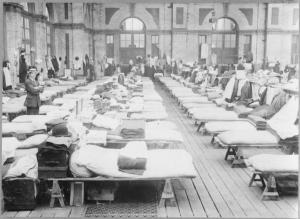

Press clippings in the archives describe the camp as ‘A Palatial Prison’ (Evening News) or dub the inmates ‘Luxurious Huns’ (Daily Mail). But Rocker’s essay tells a very different story about daily life as an interned civilian, stressing the lack of privacy in the huge, open-plan dormitories – which the prisoners eventually tried to solve by constructing makeshift huts around their beds – and the shock of being uprooted from family, friends, and work.

What stopped me in my tracks, though, was Rocker’s description of the cultural life of the camp. This section describes a series of weekly lectures given by a well-known socialist author (presumably Rocker himself), the camp’s musical concerts and amateur dramatics, and ends with an account of the prisoners’ film shows. It’s an eloquent, funny, and revealing passage, that has a lot to say about the capacity of cinema (or ‘the Kino’) to transport its audiences, and about how personal tastes can be shaped and tested by extraordinary circumstances. Here it is, as it appears in the original version assembled by Rocker’s son, a copy of which is held in the British Library (who I hope don’t mind me quoting it at length):

…there exist a number of organisations and groups, which have grown from the initiative of the men themselves, and these – each in its own way – serve to keep up the general spirits. The oldest of these institutions is that of the Literary, and Cultural-History Lecture Series, which a well-known socialist author holds regularly each week in the Theatre since July 1915. They are patronised by a fairly numerous and interested audience.

Two months later the “Konzert Verein” was founded, in which most of the interned musicians participate. It developed with surprising speed, and stood under the direct protection of the last Commandant, who was himself a great lover of music. But it was not only this personal fondness which made the Commandant patronise the “Konzert Verein”; he was strongly convinced that music acts upon the “moods” of the prisoners in a highly beneficial manner. Since its foundation, this Society has given weekly concerts in the Theatre, which are for hundreds of the Prisoners a wonderful mental recuperation, which cannot be estimated too highly.

At this place also, must be noted the Amateur Theatrical Society, which seeks, through its productions to entertain the Camp. Unfortunately there is a lack of talent, and of a planfully conducted artistical management. Most of the productions were very commonplace, and left much to be wished for, regarded from a purely artistic standpoint. For several months this society has almost entirely ceased its activities.

Several other organisations which chiefly have a sporting aim, as the Turn Verein (Gymnastic Association), the Football Club, etc., formerly enjoyed a strong membership. To-day, however, these bodies are practically non-existent as the great restrictions placed upon the food of the Camp considerably cool the sporting fever.

A retrogression, it must be said, is taking place in all the different undertakings of the various organisations. This is chiefly to be explained by the long duration of the internment. Lectures and Concerts are to-day less frequented than two or even one year ago. The dull pressure of the internment brings with it that the men lose in time all interest in any undertaking whatsoever.

The only institution which makes an exception to this painful rule and retains up to the present day the lively sympathy of the prisoners, is the “Kino”. It exists since 1915, and was received by the whole Camp with great joy. For a lengthy period, only one performance was given weekly, and it was always very well attended. But even later when two weekly “Kino evenings” were instituted, the result as regards attendance remained the same. And I am convinced that even if they were given still more frequently, the number of the audience would still remain as high as ever. The reason for this characteristic fact is moreover, easily explained. It is not here the attraction which the “Kino” exercises for itself, but the consequence of a very natural psychological process. No other entertainment or occupation of whatever nature it may be, is able to make the Prisoner forget his surroundings entirely. Whether he is employed in the workshop or studies at the school, whether he follows some sport, or listens to the sounds of music, always there is a certain something which makes him ever conscious of the narrow confines of his captivity. The “Kino” also, is not always able to suppress this gnawing feeling entirely, but it frees him more than all else, from the oppressive ban of his daily surroundings. It is, so to speak, a link with the outer world, which, though likewise resting upon a delusion, enables him nevertheless to forget for a while the leaden monotony of his surroundings.

In his thoughts he lives himself in the landscapes which pass before his eyes; he mingles with the crowds at the railway stations, boards ships and trains, and takes personal part in the dramas that take place before him. What the fairy-tale is to the child, that is the “Kino” to the Prisoner.

I knew quite a number of well educated men including artists and men of aesthetic taste, who would formerly never have entered a “Picture Theatre”, nay, who are even now antagonists of this institution generally, regarding it as a danger to the real art of the stage, but who, during internment, have become regular “Kino-goers”. And although they pass the most condemning judgment at the conclusion of each performance, and state emphatically that this was the last one they patronised, they still come again at the next one. They are, in spite of all, subject to the same psychological laws as their fellow-comrades-in-adversity, and the purely human is yet stronger than any abstract conception of art.

The pamphlet I first read Rocker’s essay in is An Insight into Civilian Internment in Britain during WWI (Anglo-German Family History Society, reprinted in an illustrated edition in 1998). The passage above comes from the typescript assembled by Rudolf Rocker, Junior, catalogued in the British Library as Alexandra Palace Internment Camp in the First World War (1914-1918). Rocker (the Elder) wrote about his experiences in London before and during internment in The London Years, translated by Joseph Leftwich (A.K. Press, 2005).

The images of Alexandra Palace are from the Air Ministry Collection at the Imperial War Museums, who also hold some remarkable sketches and paintings by one of the Alexandra Palace internees. The image at the top of the post shows sleeping quarters in the Great Hall at Alexandra Palace, © IWM (Q 64157).