Here’s a fictional trip to the pictures. About halfway through Hitchcock’s 1936 film Sabotage, Ted, a greengrocer’s assistant played by John Loder, spots a shady character going into the cinema next door. The woman at the box office (Sylvia Sidney), who is also the owner’s wife, throws him a flirty smile and lets him sneak into the auditorium for the price of an apple – he gives the uniformed usher another apple for good measure.

The poster outside the cinema advertises a Hollywood Western called Two Gun Love, featuring the fictional cowboy star Tom McGurth. But, when Ted gets inside, the film being projected looks and sounds like a British comedy – perhaps the ‘B’ movie shown before the main feature. As with a later clip from Disney’s Who Killed Cock Robin?, the scene that Ted walks in on acts as a counterpoint to the main action. Man (putting a piece of paper into the fire): “Well, all our troubles are over now.” Woman (pointing at the fire in horror): “Oh!” The laughter of the cinema audience provides a backing track to the sequence that follows, bumping up against the growing sense of tension.

The camera follows Ted as he carries on walking past the front row of seats, through a set of curtains, and behind the screen.

In an earlier age, cinemagoers at some venues could pay a reduced rate to watch from behind the screen like this. But not at the Bijou, it seems. And, in any case, Sabotage would be a very different kind of film if Ted really had just wandered in to see the evening’s show.

In fact, Ted isn’t a greengrocer’s assistant at all, but Sergeant Ted Spencer of Scotland Yard, in pursuit of a man suspected of a being involved in a terrorist plot. Masked by the sound of the speakers, he climbs up to a window to listen in on the shady character’s conversation with Mr Verloc, the cinema owner. But he is caught in the act. Stevie, the third member of the Bijou’s resident family, watches from the window as Ted tries to bluff his way out of a room full of conspirators.

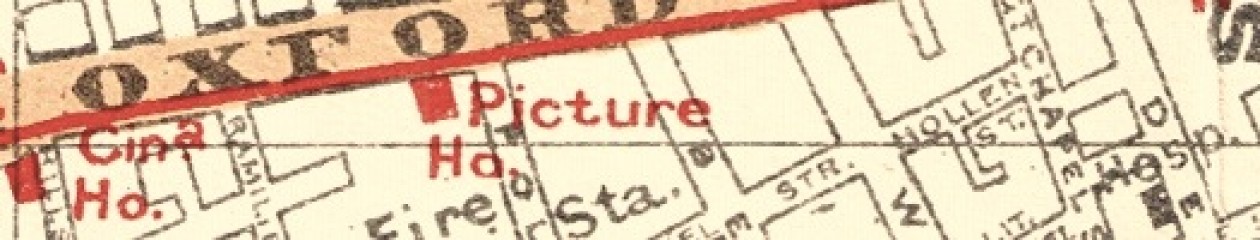

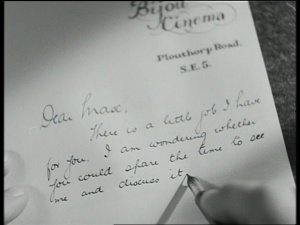

A note on the location: in Joseph Conrad’s Secret Agent, the novel on which Sabotage is based, Mr Verloc is not a cinema owner, but the proprietor of a grubby bookshop. The Bijou is the invention of Hitchcock, screenwriter Charles Bennett, and art director O.F. Werndorff. In adapting Conrad’s novel, the film also shifts the location of the Verloc family from Soho to South London. The Bijou stands on the non-existent Plouthorp Road, somewhere in the SE5 postal area around Camberwell according to Mr Verloc’s headed notepaper.  This district had seen at least one Bijou prior to 1936 (the London Project website lists a Bijou Picture Theatre on Denmark Hill that was active before the First World War), and it’s tempting to speculate whether there was a particular real-world model for the cinema in Hitchcock’s film. What matters more, I suspect, is the name in general. Bijou (French for ‘jewel’) had been a popular choice for the first wave of permanent cinema buildings in the 1910s. At the time, it was a way of connoting luxury, elegance and sophistication. By the 1930s, though, this seems to have translated to pokey and out of date. The cinema in Sabotage is a regular ‘flea pit’ – a time warp or dead end (quite literally for some of the characters). Its companion location in this version of the story – another of the film’s inventions – is a run-down ‘bird shop’, north of the river in Islington, where Mr Verloc sources his explosives. The Bijou and the ‘bird shop’ are survivors from another age. In both places, the inhabitants seem well and truly trapped.

This district had seen at least one Bijou prior to 1936 (the London Project website lists a Bijou Picture Theatre on Denmark Hill that was active before the First World War), and it’s tempting to speculate whether there was a particular real-world model for the cinema in Hitchcock’s film. What matters more, I suspect, is the name in general. Bijou (French for ‘jewel’) had been a popular choice for the first wave of permanent cinema buildings in the 1910s. At the time, it was a way of connoting luxury, elegance and sophistication. By the 1930s, though, this seems to have translated to pokey and out of date. The cinema in Sabotage is a regular ‘flea pit’ – a time warp or dead end (quite literally for some of the characters). Its companion location in this version of the story – another of the film’s inventions – is a run-down ‘bird shop’, north of the river in Islington, where Mr Verloc sources his explosives. The Bijou and the ‘bird shop’ are survivors from another age. In both places, the inhabitants seem well and truly trapped.

There’s a section on Sabotage in Charles Barr’s English Hitchcock (1999), which discusses the cinema scenes. Steven Jacob’s book on Hitchcock’s architecture, The Wrong House (2007), gives a diagram of the Bijou’s layout. For a different perspective, see the second instalment of Jon Burrows’s two-part article ‘Penny Pleasures’ (2004) in the journal Film History, which traces the real and imagined connections between cinemagoing and terrorism in some of London’s earliest film venues.