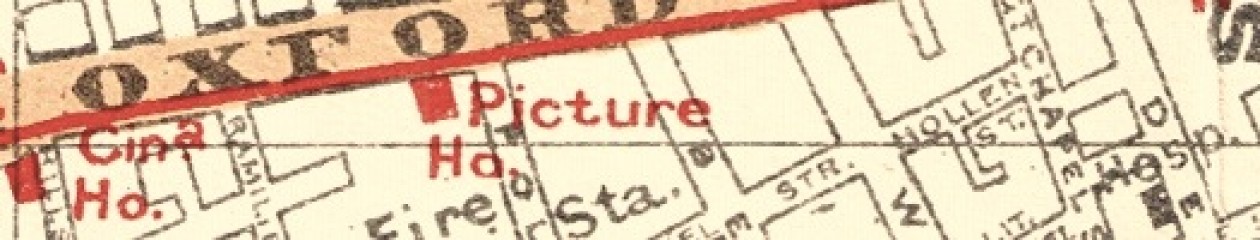

The Trocadero, known locally as the ‘Troc’, opened on the New Kent Road on 22 December 1930. It was a ‘super cinema’, providing seats for more than 3,000 patrons, a large stage for variety acts and space for what was then Europe’s largest Wurlitzer organ.

Named after the famous restaurant on Shaftesbury Avenue, the aim was to recreate West End luxury for South London audiences – a feat the venue’s original owners, Hyams and Gale, described as ‘Taking Piccadilly to the Elephant and Castle’.

The inside of the Trocadero, designed by the architect George Coles, was decorated in Renaissance style, with a vast balcony and curved ceiling. The mirrored waiting rooms were also a selling point, offering shelter from the traffic of what was one of London’s busiest junctions.

‘The Trocadero was famous, it was a beautiful palace. It was a dream palace. People worked hard and there wasn’t a lot of leisure, but you went to the cinema to see a western, gangster, musical comedy … the cinema was part of that magic. You went in and you were transported with chandeliers, gold staircases … looking back it was sheer escapism…’

Bobby Dow, interviewed for the Picture Palace Project, quoted in Southwark News, 29 August 2013

The cinema became part of the Gaumont chain in 1935. It suffered some bomb damage and temporary closures during the war, but survived more or less intact, although there was much devastation to the surrounding area.

In the postwar years, the threat of destruction was more likely to came not from bombs but from audiences. By the end of the 1950s, the Trocadero had become a hang-out for Teddy Boys and Teddy Girls from the area, who were notoriously critical, and occasionally violent, towards visiting live acts (Cliff Richard was apparently pelted with coins when he visited).

Trocadero audiences made national news in September 1956, when screenings of the Bill Haley film Rock Around the Clock sparked riots in the auditorium. This followed a spate of similar incidents in cinemas around London and other parts of the country. On one of the worst nights of what the press dubbed the ‘rock’n’roll’ riots, audiences at the Trocadero slashed seats, while people outside the cinema threw fireworks and bottles at the police.

‘There was dancing in the aisle to Rock Around the Clock and trying to get out of your seats, and the usherette used to smack you on the head, “sit down”! Outside the older boys and us used to be rocking the cars, to try to tip them over. It really kicked off at the Elephant over that film!’

Bill Leigh, interviewed for the Picture Palace Project, quoted in the Southwark News, 29 August 2013

In 1963, the cinema was demolished, along with much of the Elephant and Castle, in a large-scale redevelopment of the area. It was replaced by a smaller Odeon cinema, designed by Erno Goldfinger, which stood until 1988. There is now a block of flats on the site. The spot’s cinema history is marked by a plaque (unveiled by Denis Norden, who worked in the Trocadero in the 1940s) produced by the Cinema Theatre Association.

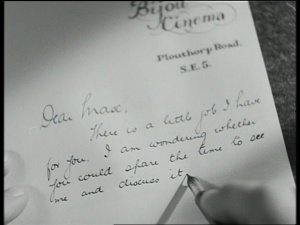

If you are in London, you can listen to more memories of cinemagoing at the Trocadero and other South London cinemas at the Cinema Museum’s Picture Palace exhibition, 21-22 September 2013.

There’s also more information about the Trocadero in these sources:

- Margaret O’Brien and Allen Eyles (eds), Enter the Dream-House: Memories of Cinema in South London from the Twenties to the Sixties (London: Museum of the Moving Image, 1993)

- Allen Eyles, Gaumont British Cinemas (London: Cinema Theatre Association/BFI, 1996)

- ‘Trocadero Cinema’ (Cinema Treasures website)

- ‘The Trocadero Super Cinema’ (Arthur Lloyd website)

- ‘Elephant and Castle, Teddy Boys and Tommy Steele’ (Blog post at Another Nickel in the Machine)

- ‘Interview: Denis Norden’, Jewish Chronicle (2008)