I’ve been revisiting some research I did into the cinema history of Soho recently as part of a study of cinema in London’s West End. Soho is a small patch of the West End – a maze of narrow streets, once home to notorious ‘rookeries’ or slums in the nineteenth century, now famous for media companies, gay pubs and clubs (it was the final stop on last weekend’s Pride celebrations), sex shops, and late-night coffee bars.

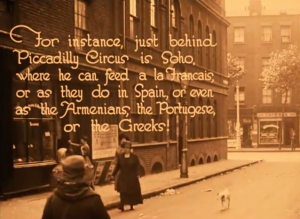

There’s a long history of immigration into this particular part of London reaching back to the arrival of the French Huguenots, and early-twentieth-century Soho has been discussed, most recently by Judith Walkowitz in her book Nights Out, as an experiment in multiculturalism.[1] By the 1900s, it had a reputation for being ‘cosmopolitan’, as in home to immigrant or ethnic minority communities, especially French, but also Italian and Eastern European Jewish. Mainly because of these cosmopolitan associations, it attracted Bohemians and was, according to Thomas Burke, where ‘respectable’ Londoners went ‘to feel devilish’. Although the rookeries were gone, it was still a cramped neighbourhood, where visitors were surprised to find lodging houses accommodating multiple families on the same floor.

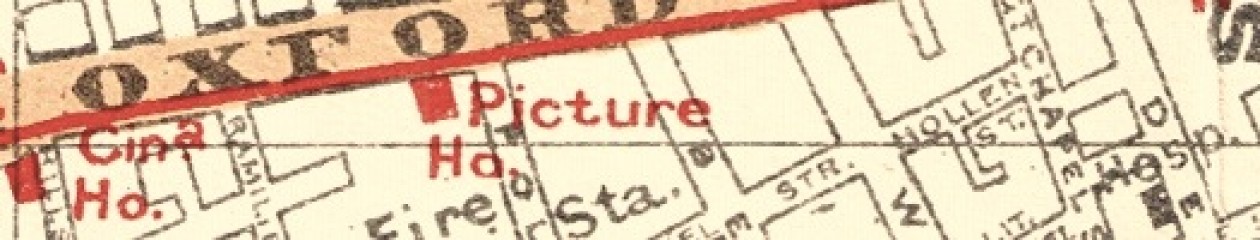

I’ve mentioned Soho before – and particularly Wardour Street – as one of the centres of the early film industry in London, especially for production and distribution companies. By the end of the 1910s, Soho was where lots of film businesses had their offices and private screening rooms. But Soho was also home to early cinemas. There were upmarket picture theatres like the Palais de Luxe (later the Windmill), on the edge of Soho, just off Shaftesbury Aveue. But there were also less prestigious venues deeper into the maze of streets, catering to Soho’s working-class population. It’s harder to find out about these places, not least because they didn’t last long, but also because they were in parts of the West End that most middle-class commentators would have thought twice about walking down (unless they wanted to feel ‘devilish’, of course). Luckily, historians of London’s cinemas have found out a bit about them,[2] and there are more clues in the archives. Here’s what I’ve found out so far about Soho’s earliest – and apparently the West End’s ‘worst’ – cinema, the Electric Cinema Theatre, 6 Ingestre Place.

The Electric Cinema Theatre, also known as the Jardin de Paris, seems to have been the earliest cinema to open in Soho, operating at least as early as October 1908. It’s half-remembered in Leslie Wood’s Romance of the Movies (he doesn’t mention its name) as a film venue opened in a converted stables, with horse stalls and cobble stones still visible from its former use. Wood may have been right about this. According to local council inspectors, the front part of the cinema was converted from a ground-floor dwelling, one of a row of terraced buildings on Ingestre Place. But the rear part was adapted from a stable yard, roughly roofed in and boarded over. The old stable had been part of a cluster of similar buildings called William and Mary Yard. The dancer and film star Jessie Matthews grew up there, and remembered that the stables housed cart horses for local market traders. Another woman who grew up nearby on Silver Place also remembered the stables being used to house performing animals – including elephants! – from the nearby Hengler’s Circus (a venue that occupied the site where the London Palladium was later built).

The cinema was operated by Mons. Felix Haté, a French-born chemist turned cinema entrepreneur, who lived outside Soho in Earls Court, and who developed a way of ‘cleaning’ scrap film stock to extend its life span.[3] This suggests that the type of films shown at the cinema wouldn’t have been new releases, but titles that had been doing the rounds on the open market for some time, possibly years, and which had become scratched and grainy from over-use. We know from 1909 police records and a 1912 company prospectus that Haté was admitting people at a penny for children and twopence for adults for something like an hour-long show, running from around 6pm to 11pm. One local resident remembered a system of red, yellow and green lights outside the cinema to tell patrons what film was playing. From a report of a fire at the cinema in 1908, we know that – at least in its earliest years – music was provided by an automatic piano.

The cinema went through various face-lifts over its relatively brief lifetime, but in the beginning it accommodated about 180 people on wooden benches, plus standing room for 40 more, with a wood-and-metal projection box over the front entrance on Ingestre Place. The floor above was used as a workshop for Haté’s film cleaning outfit. According to the 1911 census, one of the other floors was home to the Kearey family – Amy, her four sons, and her husband Henry, who listed his job as a cinematograph show ‘porter’, or custodian. Thanks to a talk from Phyll Smith (@theautist) at the fantastic What Is Cinema History? conference in Glasgow, I now know that it was fairly common to have live-in cinema custodians in this period. Perhaps Amy and her children also helped out in the running of the cinema.

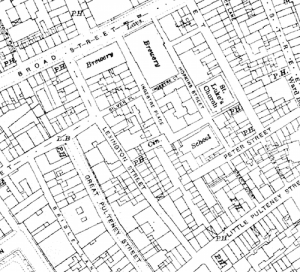

When the Metropolitan Police were asked to name the ‘best’ and ‘worst’ cinemas in their districts in November 1909, the local police branch named the Electric Cinema Theatre as the ‘worst’. There hadn’t been any complaints about crime or disruption at the cinema, although a few later mentions in council minutes suggest that local residents were sometimes irritated by children from the cinema playing outside in the street, and one neighbour at 7 Ingestre Place complained in the summer of 1912 that the cinema was staying open as late as 1am on weekdays. But it’s probably safe to assume that, for an outsider, a converted stables in Soho didn’t compare favourably to cinemas elsewhere in more affluent parts of the West End. The police inspector in 1909 described the location as ‘a very thickly populated and overcrowded neighbourhood, amongst poor tenement dwellings’. (There was also a brewery at one end of the street and a council school at the other.) Whereas the policeman saw middle-class shoppers at a nearby cinema on Oxford Street (the Cinema de Paris), the Electric Cinema Theatre was ‘Frequented by poor class Jewish, French and English youths, girls and some adults’.[4] In her history of Soho, Judith Summers writes that, in general, different ethnic populations in the area co-existed, but didn’t necessarily interact with each other. But ‘children of all nationalities and religions mixed together freely at school and in the streets’ – and, as the police report suggests, also in the cinema.[5]

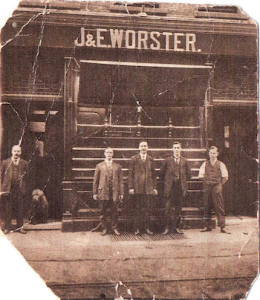

We can guess from company records (Haté launched his businesses as a joint-stock venture in 1912) that the cinema carried on trying to appeal to local residents in what the company prospectus called the ‘Cosmopolitan quarter’ of Soho. Haté kept his prices low (still one or two pence in 1912) in order ‘to meet the needs of the immediate neighbourhood’.[6] Some of his investors were very local, too. William Worster, the licensee at the Fountain Inn pub (also known as the Lion Tap) at the north end of Ingestre Place was one of the company directors. But there were also investors from Paris, presumably where Haté had connections, and Kensington, where he lived. By the start of 1912, he had also acquired another cinema – the Munster Electric Theatre in Fulham – making the Ingestre Place venue part of a (very small) cinema chain. In the summer of 1910, the Electric Cinema Theatre was also doubling as the London Cinematograph College and Situations Bureau, a training school and employment agency for cinema projectionists, according to a surviving advert.[7]

Haté was forced to make changes to the venue when the Cinematograph Act (1909) came into force and the local council began to regulate cinema exhibition more forcefully. He submitted various plans for altering the cinema to suit the council’s requirements, and he was also keen to expand it. Among the plans for refurbishment was a very ambitious proposal to buy up a chunk of Lexington Street behind the cinema and construct a large entertainment complex, with space for a cinema, as well as boxing, wrestling and sideshows, and which would also incorporate a restaurant with a licence for drinks (to be inherited from a pub at 24 Lexington Street, which would be demolished in the scheme). Altogether the proposed venue was to accommodate 3,100 people. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the plans were rejected by the council on various grounds, including the fact that ‘the streets generally in the neighbourhood are unusually narrow’.[8] In the end, the council approved a much more modest rebuilding project, involving reversing the layout of the auditorium (so that the audience now faced out onto Ingestre Place) and demolishing an adjacent stable block to make room for a second exit. The revamped cinema, newly licensed as the Jardin de Paris, was open for business in January 1913.

Despite the revamp, the proximity of the chemical works over the cinema was an ongoing problem for the council, and in November 1913 they threatened Haté with legal action unless he shut it down. The company prospectus from the previous year suggests that the chemical side of his business wasn’t actually making that much profit. But, if Haté continued to fill his programme with old, second-hand films, then it must have been handy to have the ‘cleaning’ facilities on-site. One local resident later claimed that Haté showed the films he was in the process of ‘cleaning’ in the cinema, which suggests that he may have been getting at least some of his films for free. Whether or not this arrangement carried on into the 1910s, I’m not sure.

The cinema itself lasted a few more years into the start of World War I. But, in May 1915, Haté’s company wound up its operations. When a member of the London Women’s Patrol Committee visited Ingestre Place in June 1916 (as part of another survey of London’s cinemas), she found the cinema closed and was told that the business was ‘broke’ by someone who thought she wanted to buy the empty premises.[9] Haté seems to have left England by this point. Two more businessmen – David Long and Robert Van Steenbergen, living outside Soho, and giving their nationalities as Italian and Belgian – planned to re-open the space as the Cinema de Paris in September 1916, but withdrew their application to the council because the plan was proving too expensive. A Jewish resident of Soho later recalled his father using the venue as a Yiddish theatre, the first of its kind in London outside the East End.[10] This might have been true. In 1917, Samuel Wenter, a ‘naturalised British subject of Russian origin’ according to his paperwork, applied to use the old cinema for concerts in aid of a Jewish benevolent society and for Talmud Torah classes, but he may have also used it for dramatic performances. When council inspectors visited in February 1917, they found theatrical scenery in the venue, and promptly declared it unsuitable for entertainments. By this point, there were obviously cinemas and theatres all over the West End. But this episode suggests that there was still a demand for entertainment in Soho itself that the rest of the West End couldn’t meet – either for something affordable, or for something that more closely reflected the cultures of the people who lived in the neighbourhood.

The building at 6 Ingestre Place seems to have remained empty after that. In the 1920s, part of it was demolished (along with William and Mary Yard) to make way for the multi-storey Lex Garage, now the Brewer Street Car Park. Oddly, there was a resurgence of entertainment on this spot in World War II, when the Lex Garage was used as an air-raid shelter. According to an unnamed resident quoted by Summers, the garage became a kind of social club for Soho-ites:

We children ran wild in Lex Garage, because it was so big. We had a lovely time. But we didn’t sleep very much. We played cards, and put on shows to say hallo to the soldiers and sailors. For us it was fun.[11]

So, some 30 years later, under very different circumstances, Haté’s dreams of a multi-purpose entertainment venue in this crowded part of Soho were partly realised.

Featured image: Soho street scene from Count Armfelt, ‘Cosmopolitan London’, in George R. Sims (ed.) Living London, Vol. 1 (1901): p. 244.

References:

[1] Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

[2] See especially Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures: Film Exhibition in London during the Nickelodeon Era, 1906-1914’, Film History, 16:1 (2004), 60-91, and ‘Penny Pleasures II: Indecency, Anarchy and Junk Film in London’s “Nickelodeons”’, Film History, 16:2 (2004), 172-97; and Allen Eyles with Keith Skone, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014).

[3] See Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures II’.

[4] Memo from the Superintendent of the Vine Street Police Station (‘C’ Division) to the Chief of the Metropolitan Police dated 2 November 1909, National Archives, MEPO 2/9172, File 590446/7, ‘Cinematograph Shows’.

[5] Judith Summers, Soho: A History of London’s Most Colourful Neighbourhood (London: Bloomsbury, 1989), p. 165.

[6] Company prospectus, July 1912, National Archives, BT 31/20750, ‘Haté’s Cinema and Film Cleaning Company, Limited’.

[7] Reprinted in Colin Harding and Simon Popple (eds), In the Kingdom of Shadows: A Companion to Early Cinema (London: Cygnus Arts, 1996), pp. 213-15.

[8] Letter from the London County Council (LCC) Theatres and Music Halls Committee to R.H. Kerr dated 4 November 1910, LCC Architect’s Department Correspondence File for 6 Ingestre Place, London Metropolitan Archives, GLC/AR/BR/07/659.

[9] Miss Gray, specimen report of the London Women’s Patrol Committee dated 21 June 1916, National Archives, MEPO 2/1691, File 976726, ‘Indecency in Cinemas’.

[10] Gerry Black, Living Up West: Jewish Life in London’s West End (London: London Museum of Jewish Life, 1994), p. 49.

[11] Summers, Soho, p. 184.